The Uncanny Valley

First heard and learned about it in my English class called Robot Visions In Fiction and Beyond at Dawson.

First introduced by professor Masahiro Mori in his essay called The Uncanny Valley.

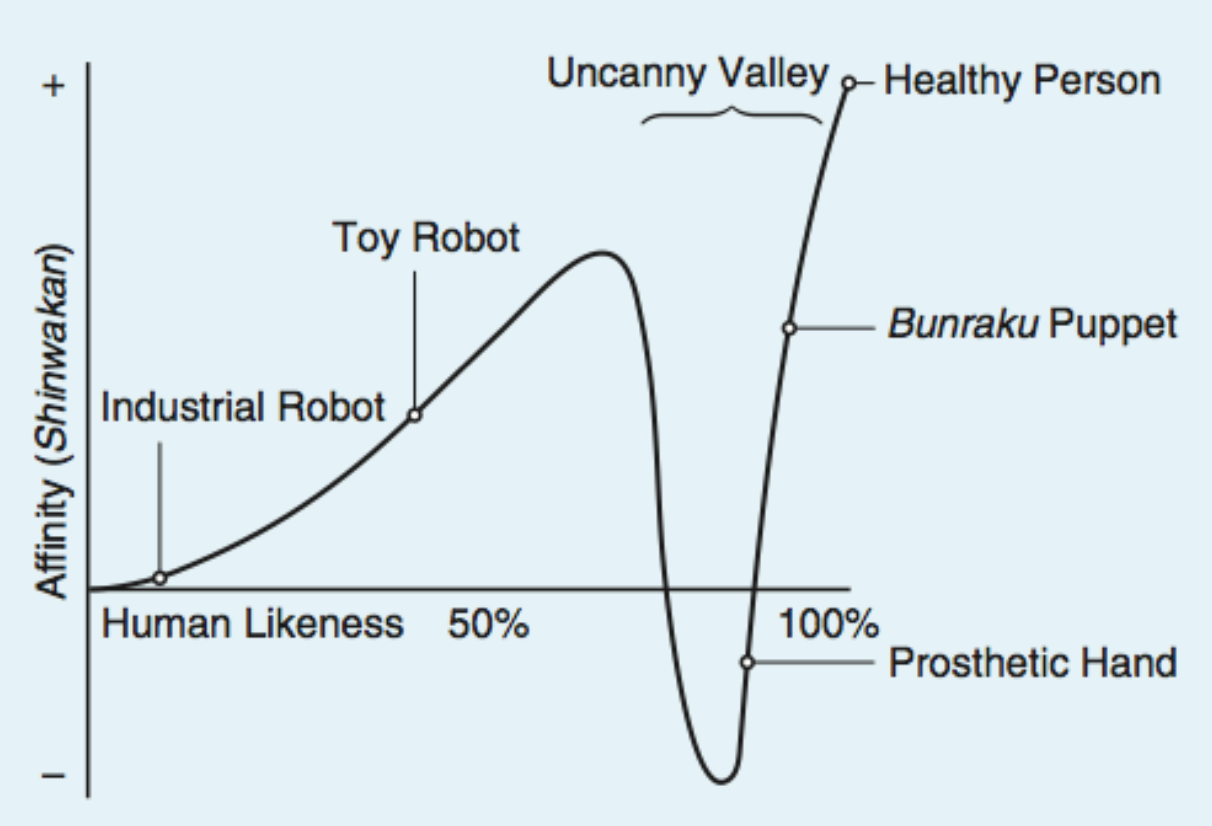

The Uncanney Valley is a hypothesized relation between an object’s degree of resemblance to a human being and the emotional response to the object. The concept suggests that humanoid objects that imperfectly resemble actual human beings provoke uncanny or strangely familiar feelings of uneasiness and revulsion in observers. “Valley” denotes a dip in the human observer’s affinity for the replica—a relation that otherwise increases with the replica’s human likeness.

A Valley in One’s Sense of Affinity

The mathematical term monotonically increasing function describes a relation in which the function y = ƒ(x) increases continuously with the variable x. For example, as effort x grows, income y increases, or as a car’s accelerator is pressed, the car moves faster. This kind of relation is ubiquitous and very easily understood. In fact, because such monotonically increasing functions cover most phenomena of everyday life, people may fall under the illusion that they represent all relations. Also attesting to this false impression is the fact that many people struggle through life by persistently pushing without understanding the effectiveness of pulling back. That is why people usually are puzzled when faced with some phenomenon this function cannot represent.

An example of a function that does not increase continuously is climbing a mountain—the relation between the distance (x) a hiker has traveled toward the summit and the hiker’s altitude (y)—owing to the intervening hills and valleys. I have noticed that, in climbing toward the goal of making robots appear human, our affinity for them increases until we come to a valley (Figure 1), which I call the uncanny valley.

Figure 1. The graph depicts the uncanny valley, the proposed relation between the human likeness of an entity and the perceiver’s affinity for it. [Translators’ note: Bunraku is a traditional Japanese form of musical puppet theater dating from the 17th century. The puppets range in size but are typically about a meter in height, dressed in elaborate costumes, and controlled by three puppeteers obscured only by their black robes. An example is shown on the cover of Robotics & Automation Magazine, above.]

Figure 1. The graph depicts the uncanny valley, the proposed relation between the human likeness of an entity and the perceiver’s affinity for it. [Translators’ note: Bunraku is a traditional Japanese form of musical puppet theater dating from the 17th century. The puppets range in size but are typically about a meter in height, dressed in elaborate costumes, and controlled by three puppeteers obscured only by their black robes. An example is shown on the cover of Robotics & Automation Magazine, above.]

The Effect of Movement

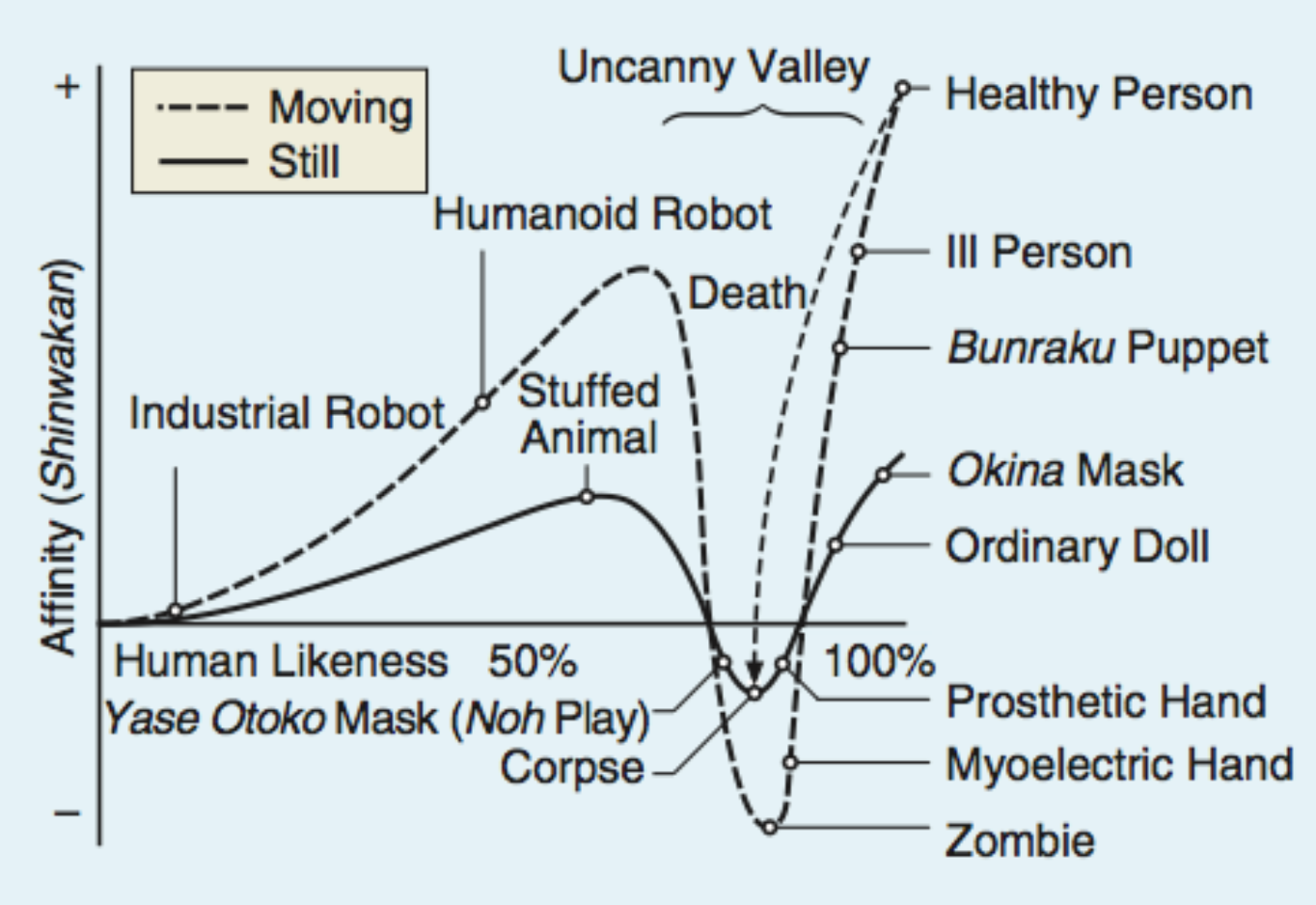

Movement is fundamental to animals—including human beings—and thus to robots as well. Its presence changes the shape of the uncanny valley graph by amplifying the peaks and valleys, as shown in Figure 2. For point of illustration, when an industrial robot is switched off, it is just a greasy machine. But once the robot is programmed to move its gripper like a human hand, we start to feel a certain level of affinity for it. (In this case, the velocity, acceleration, and deceleration must approximate human movement.) Conversely, when a prosthetic hand that is near the bottom of the uncanny valley starts to move, our sensation of eeriness intensifies.

Figure 2. The presence of movement steepens the slopes of the uncanny valley. The arrow’s path in the figure represents the sudden death of a healthy person. [Translators’ note: Noh is a traditional Japanese form of musical theater dating from the 14th century in which actors commonly wear masks. The yase otoko mask bears the face of an emaciated man and represents a ghost from hell. The okina mask represents an old man.]

Figure 2. The presence of movement steepens the slopes of the uncanny valley. The arrow’s path in the figure represents the sudden death of a healthy person. [Translators’ note: Noh is a traditional Japanese form of musical theater dating from the 14th century in which actors commonly wear masks. The yase otoko mask bears the face of an emaciated man and represents a ghost from hell. The okina mask represents an old man.]

We hope to design and build robots and prosthetic hands that will not fall into the uncanny valley. Thus, because of the risk inherent in trying to increase their degree of human likeness to scale the second peak, I recommend that designers instead take the first peak as their goal, which results in a moderate degree of human likeness and a considerable sense of affinity. In fact, I predict it is possible to create a safe level of affinity by deliberately pursuing a nonhuman design. I ask designers to ponder this. To illustrate the principle, consider eyeglasses. Eyeglasses do not resemble real eyeballs, but one could say that their design has created a charming pair of new eyes. So we should follow the same principle in designing prosthetic hands. In doing so, instead of pitiful looking realistic hands, stylish ones would likely become fashionable.

As another example, consider this model of a human hand created by a woodcarver who sculpts statues of Buddhas (Figure 4). The fingers bend freely at the joints. The hand lacks fingerprints, and it retains the natural color of the wood, but its roundness and beautiful curves do not elicit any eerie sensation. Perhaps this wooden hand could also serve as a reference for design.