PD8 - Intercultural Skills

Assignments

Assignment 1: Self-Assessment of Cultural Competence (20%)

In Part 1 of this assignment, you will review the results of the three self-assessments you took in Unit 2. You will then reflect on your overall level of cultural competence along with some of your strengths and/or areas for improvement. You will also consider where you would place yourself on the Intercultural Development continuum. Note that you will return to your answers in this assignment when completing your final Major Reflective Report.

In Part 2A of this assignment, you will use the DEAL model to reflect on a time when you made a flawed assumption (i.e. demonstrated bias) about someone. Information on how to use the DEAL model to reflect can be found on the How to Write a D.E.A.L. Reflection page.

In Part 2B, you will read the article Yes, You Have Implicit Biases, Too and consider how you can counter these when interacting with others.

This assignment is worth 20% of your overall grade. For information about how you will be evaluated, please refer to the Assignment 1 Rubric. Rubrics can be accessed by clicking Resources on the course navigation bar above and then Rubrics. You can then preview the rubric.

Assignment 2: Exploring Cultural Values (15%)

To complete this assignment download the Assignment 2 file.

In Part 1 of this assignment, you will answer a series of three questions that explore your cultural values, how they are both similar to and/or different from those around you.

In Part 2 of this assignment, you will learn about some research on how cultural values impact self-presentation and will consider how this might impact job interviews. In this case, you will get to choose 2 out of 4 questions to answer.

This assignment is worth 15% of your overall grade. For information about how you will be evaluated, please refer to the Assignment 2 Rubric. Rubrics can be accessed by clicking Resources on the course navigation bar above and then Rubrics. You can then preview the rubric.

Assignment 3: Intercultural Communication (15%)

This assignment is a 15 multiple-choice question open-book quiz covering the content in Units 4 and 5.

This assignment is worth 15% of your overall grade.

Assignment 4:

Units

Unit 2: Developing Cultural Competence

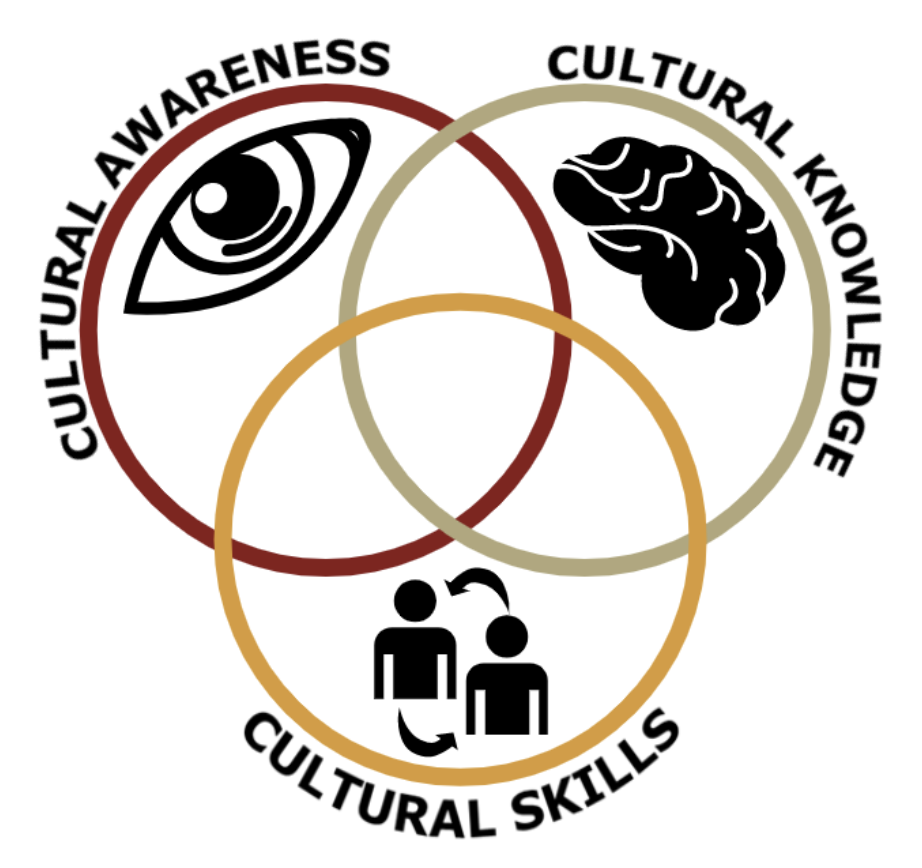

- Models of cultural competence generally include between 3 and 5 dimensions. In this module, we’ll focus on 3 pillars of cultural competence. Researchers generally agree that to be culturally competent, an individual needs the following:

- Cultural Awareness:

- To be culturally competent, one needs to be aware of their own cultural conditioning that affects personal beliefs, values, and attitudes. In other words, cultural awareness starts with reflecting on conventions and practices that each of us takes for granted in our own culture.

- One of the keys to being culturally aware is to pause whenever you are about to judge someone else’s behavior. See if you can figure out the underlying values or motivations that are driving that behaviour.

- Score 37 out of 45

- Cultural Knowledge:

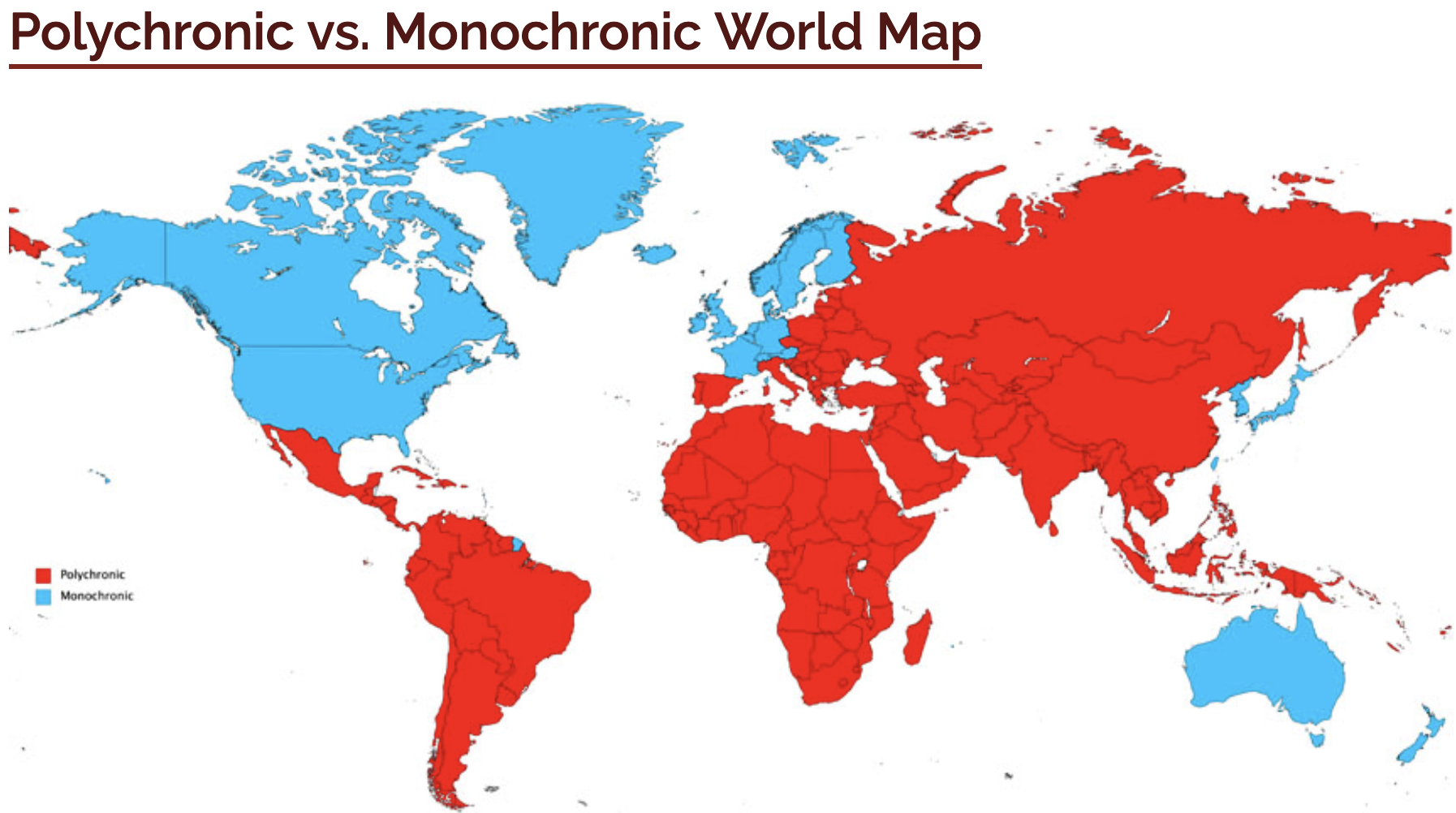

- To be culturally competent, one needs an understanding and knowledge of the worldviews of culturally different individuals and groups. There are so many things one can learn about the culture of a particular place. The following aspects below, among other things, all contribute to culture:

- In this course, we will be looking at the aspects of culture that lie beneath the surface – values, norms and assumptions – and how these impact communication and workplace relationships, among other things.

- Score 9/11

- To be culturally competent, one needs an understanding and knowledge of the worldviews of culturally different individuals and groups. There are so many things one can learn about the culture of a particular place. The following aspects below, among other things, all contribute to culture:

- Cultural Skills

- To be culturally competent, one needs to be proficient in the “use of culturally appropriate intervention/communication skills” and be able to self-adjust one’s actions based on the context of an intercultural situation.

- All the knowledge in the world does no one any good if it can’t be applied. In later units, we will work through a variety of scenarios to develop your skills in both interpreting cultural differences, adjusting your own behavior, and communicating effectively.

- The following skills are important for developing your intercultural competence:

- Perspective taking

- Testing the validity of our assumptions

- Self-assessing and self-adjusting our behaviours

- Workplace tip: There are a lot of intercultural skills that we could work on as we get a better understanding of the richness and diversity of cultural norms and conventions. Our advice: start small! A good first step is to identify a practice or behaviour that is noticeably different from what you are used to or what you have previously experienced (e.g., greetings, small talk, giving feedback, making appointments, offering compliments or apologies) and explore how this practice varies across cultural contexts. After that, you can think about ways you can use this knowledge to adjust your behaviour if you were to interact with colleagues who don’t share your cultural background. Intercultural skills are transferable skills since they help us learn how to deal with unexpected experiences and encounters of all kinds.

- Score 31/40

- It takes a lot of conscious and intentional work to understand cultural differences and to adjust behaviours to a new culture. We encourage you to approach cultural differences as a strength rather than a deficit. For example, your colleague with an accent may speak more than one language.

- Unconscious Biases & Stereotypes:

- No matter where we are on the spectrum from ethnocentrism to acceptance, we all have cultural biases. Most of the time, we are not even aware of these biases.

- Discrimination

- It must be emphasized that stereotypes and biases are attitudes or beliefs, not actions. What happens, then, when we act on our biases? One of the consequences of this is discrimination against those who are different. We may think that employers in culturally diverse North American cities such as Toronto, Vancouver, or Chicago are skilled at recognizing and avoiding discrimination. However, research on hiring practices tells us otherwise. The following are a few examples of studies that revealed subtle types of discrimination that even well-meaning individuals sometimes fall into.

- Name-based Discrimination: A large Canadian study found evidence of name-based discrimination in hiring. In 2012, researchers from the University of Toronto sent thousands of identical resumes to employers in Vancouver, Montreal, and Toronto. The only difference between them was the names of applicants! Some had Anglophone names, others, non-Anglophone names that are common outside of North America. Applicants with English names were more than 35% more likely to be invited to an interview than job applicants with Chinese, Indian or Greek names!

- Names matter. Our names are a key part of our identity but very often their importance is underestimated. Those whose names are routinely mispronounced or changed feel excluded and embarrassed. Some people opt to adopt a ‘anglo-sounding’ name or adapt their name to ease interactions. Making an effort to learn how to correctly pronounce the names of people we interact with is an important intercultural practice which contributes to inclusive and respectful interactions.

- If you are a native speaker of English, keep in mind that just like how Anglophone names do not have universal spellings or pronunciations, neither do international names. Here are a few tips and strategies to keep in mind regarding people’s names:

- Don’t make assumptions about someone’s gender or ethnicity based on their name.

- Avoid saying that someone’s name is “difficult” or “tricky.”

- When communicating verbally, ask the name-bearer how to pronounce their name and ask them to correct you if you mispronounce their name. In written communication, see what name people use in their email sign-offs as it might be different from the name in their email address.

- In some cultures, last names come first. As a result, when writing in English, individuals from China and other countries with last-name-first convention might still write their surname first.

- In some countries (e.g., Ethiopia) people don’t have last names. When moving to Canada or other western countries, people may use their father’s name instead of a last name.

Unit 3: Understanding Cultural Values

What are Cultural Values?

People from the same cultural group share beliefs and attitudes about what is appropriate or desirable (although individuals do not necessarily share all cultural beliefs and they might feel strongly about some but not all).

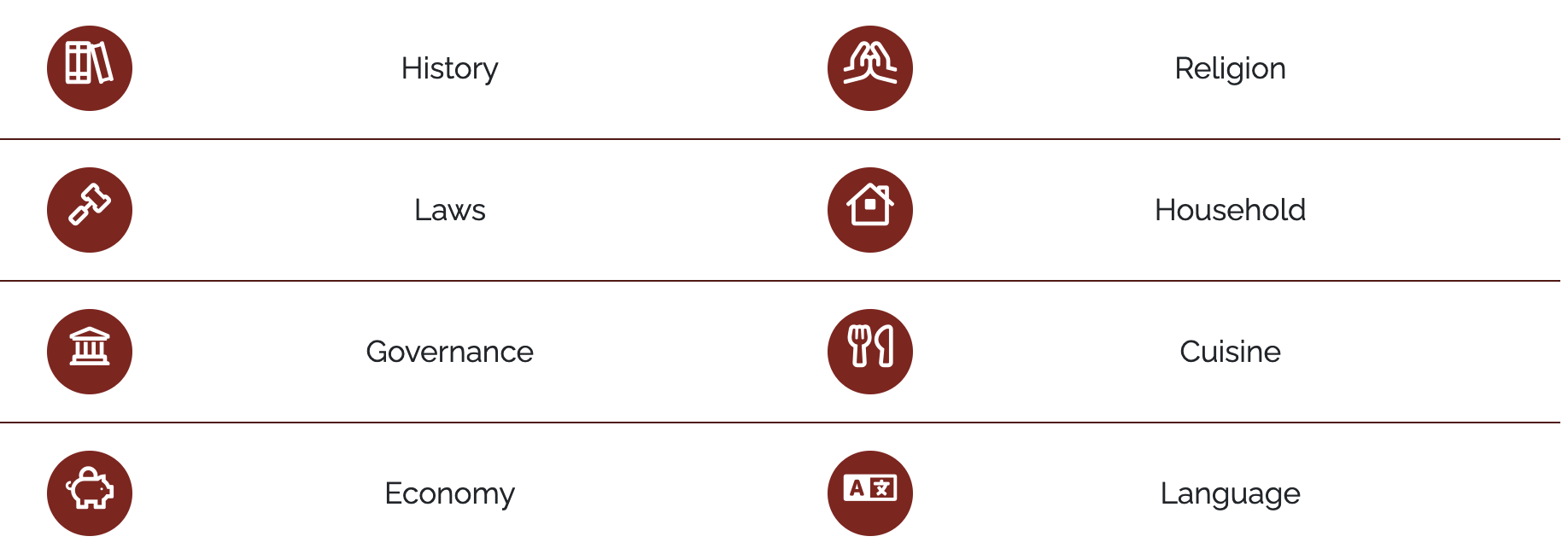

Shared cultural beliefs are based on the answers to a set of important questions that every society needs to answer, such as:

- How do we see ourselves?

- How do we relate to other people?

- How do we understand and use time and space?

- How do we organize ourselves and distribute responsibility?

- Do we as a group prioritize relationships or efficiency?

Each culture answers these important questions differently. The answers to these questions are referred to as cultural values.

We do not see our cultural values, yet they are important. They tell us what to do and expect in a given situation. For example:

When one does something that does not fit the normative expectations of a cultural community and ideas of what is ‘appropriate’, those in the cultural community assume that the individual is being deliberately difficult or simply rude.

In intercultural contexts, knowledge of cultural values gives us useful clues for interpreting observable behaviors (e.g., greeting, queuing, striking up a conversation with a stranger or smiling at them). Let’s look at two examples.

Example

In Sweden, understanding the Swedish concept of lagom provides important insight into the underlying cultural values and attitudes Swedes hold towards work-life balance. Lagom means “not too little, not too much, just right.” In her popular book “Lagom: The Swedish Secret of Living Well”, Lola Akinmade Akerstrom explains what lagom looks like in the workplace:

“Think of lagom as an imaginary scale that always needs to be balanced… Working too much is an antithesis of lagom so a very quick way of applying the concept at work is to take regular breaks. In Sweden, taking a break with coffee and maybe a sweet treat with colleagues even has a name - fika. It helps you recalibrate your day so you’re not working too much.”

Example 2

Another example of an important cultural concept that is embedded in core cultural value is guanxi in China. For anyone working in China, it is essential to understand the cultural concept of guanxi, which refers to a web of social relationships (or personal social network) build around trust, reputation, and reciprocity.

This cultural concept is deeply rooted in the important cultural value of interdependence, in-group obligations, and connectedness. It is important to understand how guanxi operates and ways in which guanxi is different from how one’s professional networks are understood and utilized in Canada.

Cultural values are something we start to pick up on, even in early childhood, through how we are raised and socialized.

- Were your parents more likely to encourage you to try something yourself or to tell you how to do it and encourage you to ask for help?

- If you hid behind your parents when you met a stranger, did they disapprove and try to get you to come out and introduce yourself? Or did they accept and even seem pleased about your hesitance?

- Were your parents more likely to discipline you by asking you to think about how your actions negatively affected others? Or by taking away a toy or giving you a time out?

- Were you allowed or even encouraged to disagree with your parents or teacher and decline activities you didn’t want to participate in? Or were you expected to do as you were told without complaint and without questions?

- Was it okay for you to enthusiastically express your emotions, personality, and preferences? Or were your parents particularly proud when you were able to conduct yourself calmly and go along with the group?

Your parents reactions gave you important information about what was or was not valued in your culture. The internalization of these values influences your behaviour and communication today. Were your colleagues or friends raised differently than you? What did they internalize as children that has formed the basis of their values today?

How might your colleagues’ values differ from your values?

- Dimensions of Cultural Variability

- The idea that national cultures can be understood through the lens of several key cultural values became popularized in the 1980s by a Dutch social psychologist named Geert Hofstede (pronounced ‘Hofstayder’). He conducted research on how workplace values of IBM employees in 40 countries were influenced by their national cultures.

- Based on his findings, Hofstede posited that cultural differences can be understood through the lens of several distinct cultural dimensions. Initially, he identified four dimensions of cultural values which became known as the 4-Dimensional (or 4D) model of national cultures. In 1991 and later in 2010, Hofstede and his colleagues expanded the original model by adding two more cultural values to create the 6D model of cultural values presented below.

- According to Hofstede and many other researchers who created similar models, all national cultures can be plotted alongside a continuum for each cultural value dimension. Each of the six scales in Hofstede’s model has two opposite cultural values (for example, the Individualism-Collectivism Scale). Since cultural values shape our approach to life and work, knowing where a culture is located along the continuum allows us to explain a wide range of behavioral and communication phenomena.

- Later in this unit, we will take a closer look at some of the most popular and well-researched dimensions of Hofstede’s model that are still used today. However, first we will explore another important area of intercultural knowledge which has to do with the culturally shaped understanding of time and time-related phenomena.

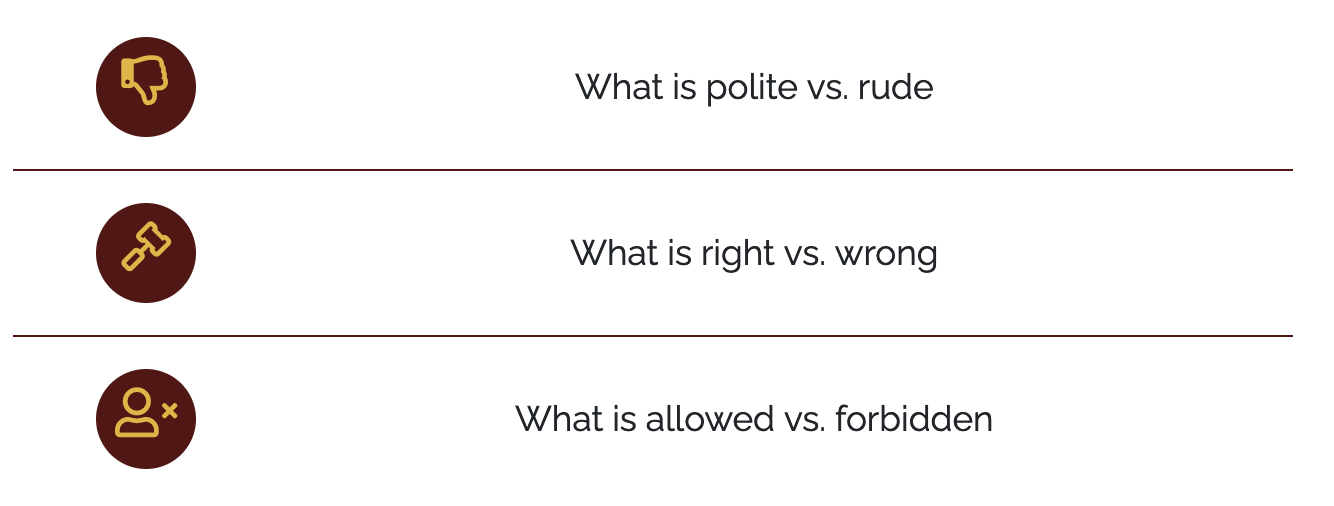

- It was the work of American anthropologist Edward T. Hall in the 1980s that offered us important insights as to how people in various cultures use and relate to time.

- Time orientation

- Let’s start with the first cultural value: time orientation. This value is a familiar and relatable one! You might be surprised to learn that there are cultural variations when it comes to time perceptions since it’s easy to think about time-related constructs as being universal.

- However, people’s ideas of time vary across cultures. Intercultural researchers tell us that one of the most difficult parts of living abroad is adjusting to the pace of life and the organization of time.

- In fact, time is one of the most fundamental differences that separate cultures. We all organize our lives around time, but we all approach time differently, and culture has a lot to do with it.

- For example, in Mexico when someone says ‘ahorita’ - which directly translates as ‘right now’ - they do not necessarily mean that the action will be performed immediately. According to one Mexican linguist, “When a Mexican says ‘ahorita’, it could mean tomorrow, in an hour, within five years or never.” (Rigg, 2017).

- To a Canadian visitor who is accustomed to a precise, linear and rapidly advancing notion of time, ‘ahorita’ can be rather confusing. However, to those who come from cultures with a more fluid and relational understanding of time, ‘ahorita’ does not have the same sense of urgency and concreteness.

- In 2003, Brislin and Kim published an interesting study that identified 10 ways in which time concepts vary across cultures. This study is a worthy read for anyone working in culturally diverse settings as it helps us understand cultural variations in punctuality, efficiency, pace of life, socializing at work, and work-life interface. A summary of the 10 ways in which cultures differ when it comes to time perception is presented below.

- Which of the cultural differences in time perception most resonate with your experience in the workplace? What strategies could you use to adjust to cultural differences in time orientations?

- The following image shows which countries/provinces tend to be more monochronic in their time orientation and which tend to be more polychronic. Although this image shows countries/provinces as belonging to one category or the other, this is not entirely accurate. Remember that time orientation exists on a continuum, so there will be variation even within the countries/provinces of one type and within individuals in each country/province.

- IMPORTANT: Even though they are divided into two discrete categories in the map above, not all countries within each category are exactly the same in terms of how they approach time. There is no absolute measure of monochronicity or polychronicity. Remember, countries are measured relative to each other. This means, for example, that even though Spain and Italy are both considered polychronic countries, they could still experience cultural differences if one is more polychronic than the other.

- REMINDER: These categorizations are based on researching large group patterns. The cultural time orientations allow us to predict how the majority of people from a particular culture would view time concepts and act in social situations. Not all individuals will manifest culturally dominant time orientation especially in professional settings that might be guided by organizational norms around time.

- Individualism-Collectivism

- We will now turn our attention to the classification system of cultural values developed by Geert Hofstede. While there are many different models of cultural dimensions / scales proposed by researchers, we will focus on Hofstede’s model since it’s most well known. In particular, we will focus on the most researched cultural dimensions in Hofstede’s model as these dimensions are critical for understanding workplace interactions.

- The first most popular dimension is known as the individualism-collectivism scale.

- This cultural dimension has to do with how we see ourselves in relation to others. Are individual goals or group goals more important? Does a culture promote self-reliance and independence, or group interest and interdependence? In other words, does the culture emphasize “I” identity or “we” identity?

- The dominant cultural pattern in Canada and the United States is, as you can probably guess, individualistic because both countries value individual merit, personal achievements, self-promotion, and assertiveness. These individualistic value tendencies, according to Hofstede’s theory, are manifested in everyday situations as well as in workplace interactions. For example, during a job interview in North America, interviewees are expected to talk about personal achievements, explain to a prospective employer their unique “selling points”, and, overall, distinguish themselves as much as possible from other applicants. In the workplace, individual ambition and initiative are prized and everyone is expected to contribute their ideas and opinions. Depending on how national cultures answer these questions, they can be classified as either individualistic or collectivistic cultures.

- Compare this to collectivistic or group-oriented cultures where the focus is on interdependence, cooperation, and success of the group (recall the Chinese cultural concept of guanxi). There is a Japanese saying: “The nail that sticks out gets hammered down.” This saying captures the group-oriented philosophy of work and life that characterizes collectivistic cultures. People in collectivistic cultures tend to use “we” and “you” more often than “I.” It is fairly common for people to get jobs and professional opportunities based on their family connections and favours. Collectivistic societies are also known for strong friendship ties, and the word ‘friend’ is reserved for the closest and most trusted circle of friends (friendships are meant to last a lifetime!). Many immigrants and international students who come to Canada and the US are surprised by the liberal use of ‘friend’ to refer to a wide circle of acquaintances.

- Families play an important role in collectivist cultures, and children are often raised by extended family. On the other hand, in individualist cultures, people tend to relocate often in pursuit of professional opportunities and are less connected to their extended families.

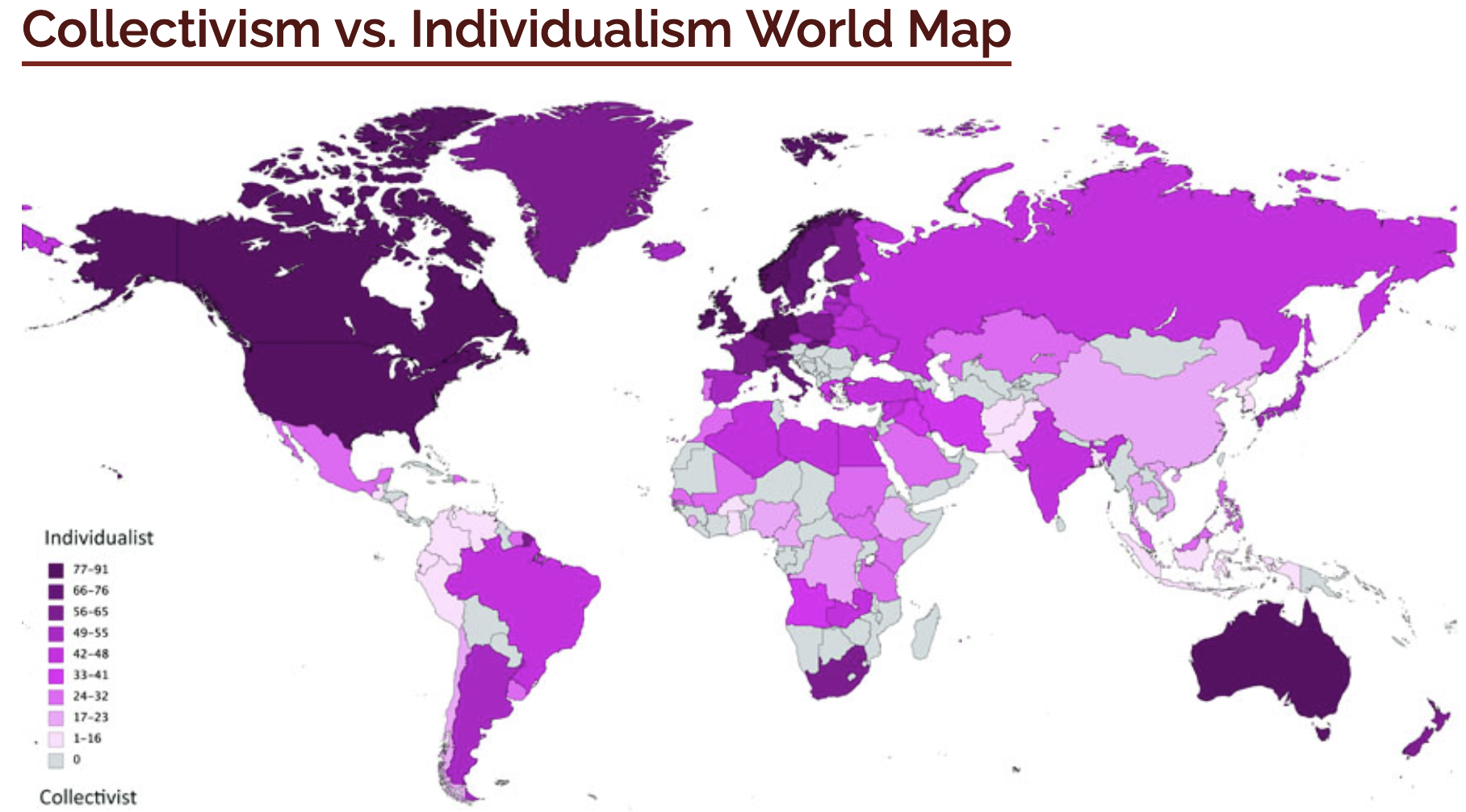

- The following image shows where countries fall on the individualism to collectivism scale. As always, remember that all cultural values exist on a continuum, so there will be variation even within countries which appear to be the same on the map and within individuals in each country.

- The following image shows where countries fall on the individualism to collectivism scale. As always, remember that all cultural values exist on a continuum, so there will be variation even within countries which appear to be the same on the map and within individuals in each country.

- Workplace Tip: In collectivistic cultures, the family name is typically placed before the given name, while in individualistic cultures, the opposite is true. For example, when the instructor introduces herself in Canada, she would say, “Hi! I am Svitlana Taraban” while in her native Ukraine, which is more on the collectivist side of this culture scale, she would be known as Taraban Svitlana. The same is true for other countries that tend to be more collectivistic. For example, Wang Mei, in Chinese would be Ms. Mei Wang in the Western style because Wang is her family name.

- Small-Large Power Distance

- The second cultural value in Hofstede’s 6D model refers to how cultures view power and authority and deal with status differences based on role, rank, or age.

- The intercultural concept known as “power distance” helps us describe how different cultures view power and authority.

- In workplace settings, power distance refers to how managers and employees relate to each other. To understand how cultures view social hierarchies and status differences, consider the following scenarios in educational and workplace settings.

- Workplace Tip: In the Canadian workplace, you would likely call your boss and your boss’ boss by their first name. Generally, superiors are expected to share power and delegate responsibilities. These strategies are used to de-emphasize power and promote symmetrical relations. As a general rule, employees do not like to be micromanaged and are rewarded for taking initiative.

- That is not to suggest that there is no power differential between managers and employees in the workplace. Certainly, status and power differences exist; however, in Canada organizational cultures tend to make them less obvious. Addressing those in power on a first-name basis as well as having everyone contribute to workplace discussions and decision-making processes are some of the strategies that we use in Canada to downplay power differences and signal less formality in unequal relationships. Entry level employees are likely to be viewed as younger colleagues and are given tasks that allow them to work rather autonomously and to interact with people of different positions in the organizational hierarchy.

- In high power distance cultures, rank and authority play an important role, and the relationships between superiors and subordinates tend to be more formal. It is common for students to have visual displays of respect for authority through common ritualized behaviors such as standing up when a teacher enters the classroom or not asking questions in front of the class. Teachers would never be addressed by their first names - proper titles and honorifics, such as Doctor or Professor, are expected. In these cultures, for example in Asia or the Middle East, being an intern or a trainee means that you are seen as a learner-in-training and that you need a lot of direction and supervision. Early career employees are expected to respect and learn from those who have more education and experience than them. They are generally not consulted in the decision-making processes. These employees are closely supervised and are not expected to take initiative.

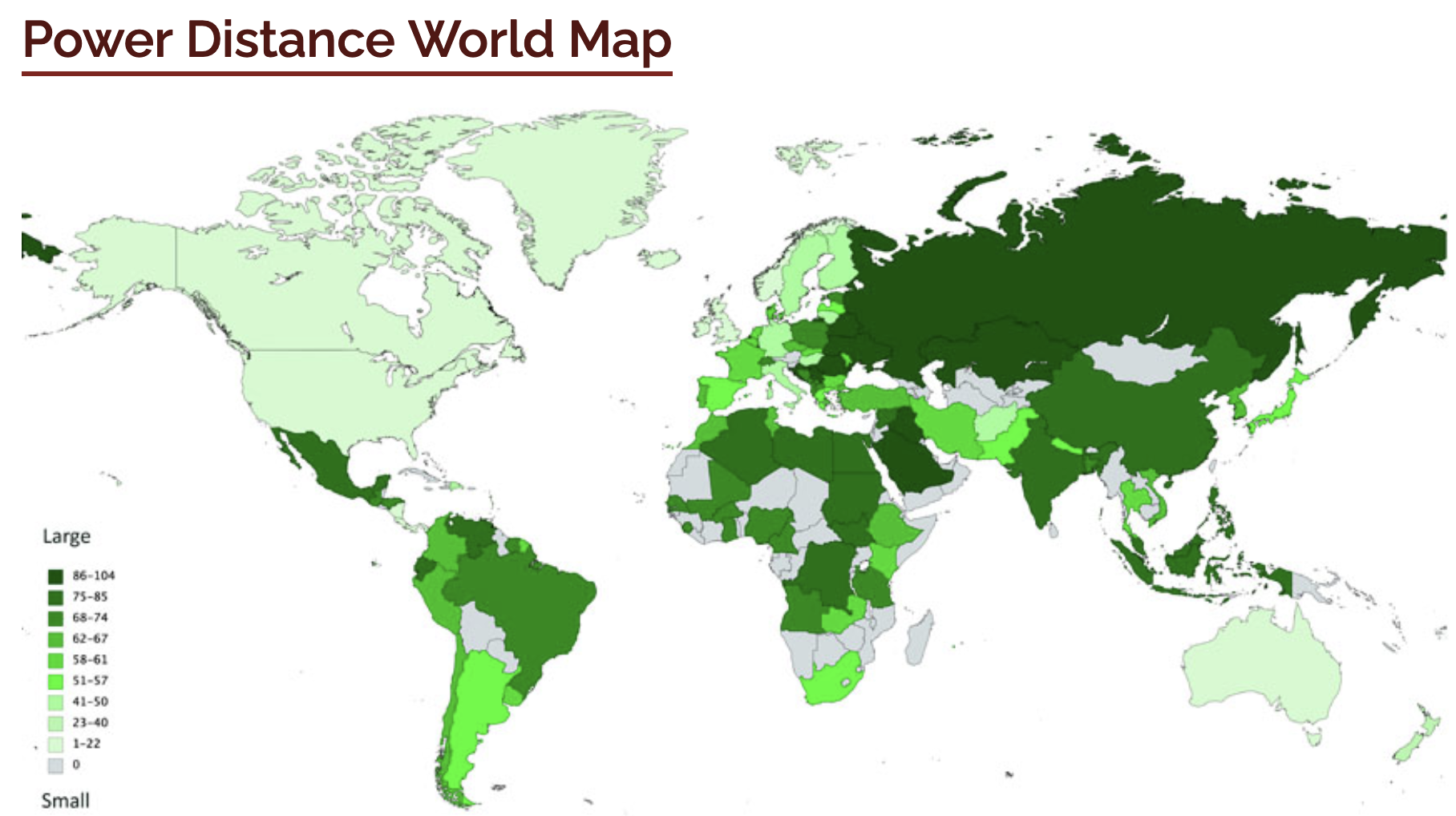

- Relative to other countries, Canada would be located somewhere in the middle in terms of power distance - it is more egalitarian than Asian, Latin American, or Arab cultures, but less egalitarian than Scandinavian countries, such as Sweden and Norway. However, there are differences even within Canada - for example, many companies in Quebec have more of a hierarchical culture and the workplace relationships tend to be more formal across power lines compared to the rest of Canada. Both individualism-collectivism and high-low power distances are useful intercultural concepts for analyzing cultural variations in the workplace. Intercultural researchers suggest layering these two dimensions – along with other contextual features and personality types - in order to unpack and interpret intercultural situations that challenge our cultural assumptions and involve unexpected or unfamiliar experiences. The following image shows where countries fall on the power distance scale. As always, remember that all cultural values exist on a continuum, so there will be variation even within countries which appear to be the same on the map and within individuals in each country.

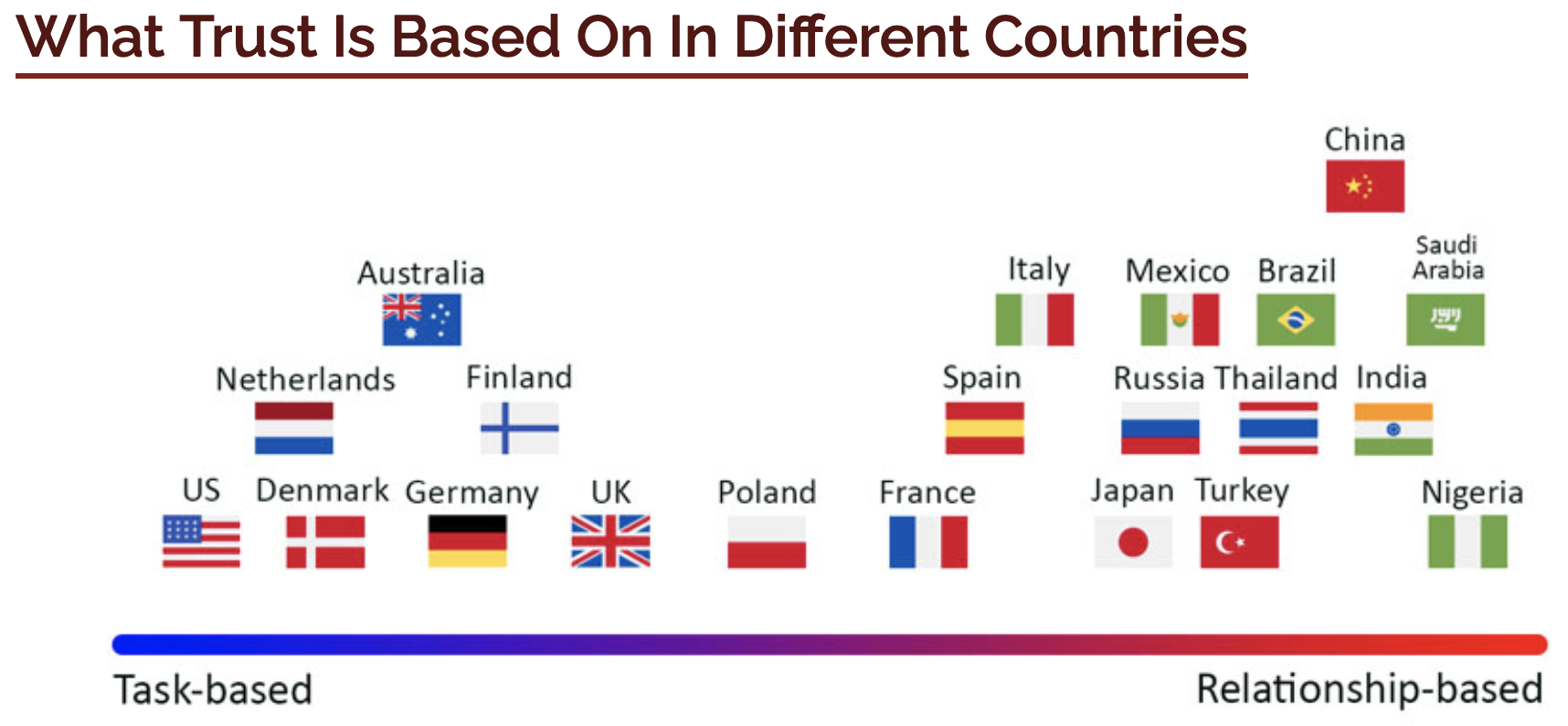

- Prioritization of Task vs. Relationship

- The fourth cultural value in this unit has to do with whether cultures prioritize tasks or relationships and whether work gets done through the skillful management of time and tasks (focus is on efficiency and deadlines) or through relationships, group connectedness, and trust building. We will briefly explore this value dimension as it is useful for understanding cultural factors in teamwork dynamics and decision-making processes.

- The following image shows where countries fall on the task vs. relationship-based scale. As always, remember that all cultural values exist on a continuum, so there will be variation even within countries which appear to be in the same area on the scale and within individuals in each country.

- Other Cultural Dimensions

- As we mentioned earlier, there were other dimensions of cultural value differences proposed by intercultural researchers (e.g. risk taking vs risk avoidance, which entails how national cultures tend to manage risk and uncertainty).

- If you are interested in a more recent cultural dimension model, we suggest exploring the GLOBE model (2004 and 2007) developed based on cultural data from 62 countries. The GLOBE model focused on the study of leadership styles and includes nine dimensions with many dimensions being similar to the ones proposed by Hofstede.

- The new dimensions introduced in this model include performance orientation (degree to which cultures emphasize performance and achievement) and humane orientation (extent to which cultures emphasize fairness and caring). The following visual summarizes the GLOBE model.

- Uncertainty Avoidance

- Institutional Collectivism

- In-Group Collectivism

- Humane Orientation

- Performance Orientation

- Assertiveness

- Gender Egalitarianism

- Future Orientation

- No matter what model you use or what dimensions you consider, remember that they are a continuum not a binary! Different countries fall in different places along a dynamic continuum of cultural values. Comparing country scores/placements on various dimensions is helpful for mapping out underlying cross-cultural differences in attitudes and beliefs.

- We can’t be experts in every culture, but understanding differences in cultural values helps us to notice cultural patterns that are operating in different situations and alert us to cultural differences. From there on, we can continue to discover cultural differences and similarities embedded in cross-cultural interactions.

Unit 4: Cultural Differences in Verbal Communication

English might be the common language in a global workplace, but communication styles vary across cultures in terms of formality, directness, role of context, expressiveness, and politeness. There are also differences in customs around greetings and expectations around small talk.

Intercultural skills you will develop in this unit include:

- Analyzing cultural differences in communication styles.

- Recognizing cultural misunderstandings based on differences in communication style.

In Unit 2, we explored how culture affects our perceptions of others. In this unit, we will look at how culture affects communication styles and discuss cultural influences on both verbal and non-verbal communication.

We will focus on four communication style categories for understanding intercultural communication:

Do people who speak different languages think differently and see the world differently?

Some scholars argue that all humans regardless of cultural and language background use the same thought processes and that languages don’t shape how we think. Other scholars argue that languages shape our cognitive and affective experiences (e.g., how we reason, make decisions, remember events, experience emotions). Researchers still don’t have a definite answer to this question, but there are interesting findings emerging from recent research on this topic. If you are interested in recent thinking on this topic, read this short article about recent research conducted by MIT and Stanford on how speakers of different languages think differently about space, time color and objects (if you prefer video content, watch this 14 min. TED Talk by the main researcher, Lera Boroditsky).

In this section, we are going to explore a few keys ways that communication differs across cultures.

- High vs. Low Context

- Instead of just telling you what high vs. low context is about, we are going to show you: One of the most famous experiments in the area of perceptual differences across cultures was conducted by researchers from the University of Michigan. Known as the Michigan Fish Test, the study by Dr. Richard Nisbett and his colleagues basically looked at how Japanese and US Americans described what they saw when shown the same picture of an underwater scene involving fish, plant life and rocks. The descriptions given by the two groups were qualitatively different in terms of which aspects of the picture the participants focused on. American participants began their descriptions by identifying a large fish and focusing their descriptions around the fish. Japanese participants began their descriptions by saying, “It’s a river” or “It’s a pond”, and reported seventy percent more background information. The researchers concluded that adults from Western cultures process information analytically, by focusing on key features, while adults from the East process information holistically. That is, Eastern cultures pay attention to context and situation. Context is important to Asian cultures, as a lot of meaning is derived from it.

- This experiment relates to the way in which some cultures require listeners to infer the meaning of what is said from the contextual details of the message. For example, the status of the speaker, body language, setting, or some elements of shared knowledge. This is called high-context communication – an important intercultural term that we will be frequently using in the course.

- High-context communicators rely on context and body language, rather than on words alone, to communicate meaning. High-context communication is subtle; therefore, listening is very important. It is the listener’s responsibility to make sense of the message. Speakers of some languages (e.g., Chinese, Japanese, French) tend to use more high-context communication strategies. Honour and shame are important concerns in social interactions in high-context cultures.

- By contrast, low-context communication (another important intercultural term) happens when the information is explicitly stated in the message and the meaning is expressed precisely. Low-context communication relies on clear and explicit messages. It is the speaker’s responsibility to make sure the message is understood. Speakers of English and German languages tend to be low-context communicators. In low-context cultures, words have precise meanings and very few words have the same meaning (for example, very few German words have multiple meanings)

- Listen to Erin Meyer, author of the Culture Map, describe some of her experiences working with teams in high and low context cultures. She explains how these communication styles fall on a continuum, just like the cultural values described in the last unit. In fact, communication style and value orientation tend to correlate. For example, collectivistic, relationship-oriented cultures tend to favour high-context communication style, while individualistic, task-oriented cultures rely heavily on low-context communication.

- When it comes to work settings, low-context cultures tend to favour direct communication. It relies heavily on protocols, procedures, and rules that are clearly spelled out for employees. All business agreements and arrangements are done in writing, typically with input from legal professionals. All parties are expected to sign agreements in writing.

- In comparison, in high-context cultures, communication is governed by relationships and trust. Business deals can be made using verbal agreements (typically over dinner) based on trust and respect and without extensive documentation that lays out contract terms.

- One good example of high- and low-communication can be found in the amount of information displayed in public spaces. Low-context cultures use a lot of clear rules, signs, detailed maps, and instructions. If you happen to be at any airport, train, or bus station in Germany, Canada, or the U.S., you will see maps and written directions. Compare this to high-context cultures where there is little formal information, and where street names and building numbers often don’t exist. There might not be a “no smoking” sign in the public space where smoking is not allowed. The individuals are expected to figure out what to do by paying attention to the context and circumstances around them (for example, what other people are doing).

- Directness

- The second useful category for analyzing cross-cultural communication is the distinction between direct and indirect communication styles. Directness refers to how explicit a speaker is about the main point and how quickly she or he moves to the point.

- In direct communication, the focus is on what is said, while in indirect communication, the focus is on how it is said.

- Direct communication style values clear and explicit messages that convey the meaning explicitly. Brevity and getting to the point quickly is important. Think about expressions such as “cut to the chase” or “straight shooter” which are often used by Canadians and Americans. They signal the value placed on direct communication. In the workplace, direct communicators are comfortable with asking questions, having frank discussions, making direct requests, and expressing disagreements during meetings. To take one example, Dutch speakers are known as very direct and straightforward communicators. There’s even a Dutch word bespreekbaarheid (speakability) which captures the importance of straight talking and freely discussing pretty much any topic.

- In cultures that use indirect communication, messages are suggested or implied rather than stated directly. Indirect communicators provide background information and details before arriving at the main point (which is implied rather than stated directly). They place high value on small talk and pleasantries before engaging in business conversations and tend to avoid public disagreements and confrontation in workplace settings. Critical feedback and refusing requests/saying ‘no’ are implied rather than expressed directly. For example, Japanese and Chinese speakers have a repertoire of strategies for saying ‘no’ which range from using words such as ‘perhaps’ or ‘maybe’ to putting things off or offering an excuse – in all cases, never saying ‘no’ directly. Examples of countries that favour direct communication include Canada, U.S., Denmark, Switzerland, Austria, Germany, and the UK. Examples of countries that favour an indirect communication style include China, Japan, India, and Pakistan.

- Direct communication style values clear and explicit messages that convey the meaning explicitly. Brevity and getting to the point quickly is important. Think about expressions such as “cut to the chase” or “straight shooter” which are often used by Canadians and Americans. They signal the value placed on direct communication. In the workplace, direct communicators are comfortable with asking questions, having frank discussions, making direct requests, and expressing disagreements during meetings. To take one example, Dutch speakers are known as very direct and straightforward communicators. There’s even a Dutch word bespreekbaarheid (speakability) which captures the importance of straight talking and freely discussing pretty much any topic.

- In many cases, direct and low-context communication go together and indirect and high-context communication go together. However, there is one area in which this is not the case and that has to do with feedback.

- Watch the following video to learn about how countries differ in terms of how directly or indirectly they tend to give feedback. Business Speaker Erin Meyer: The Language of Negative Feedback

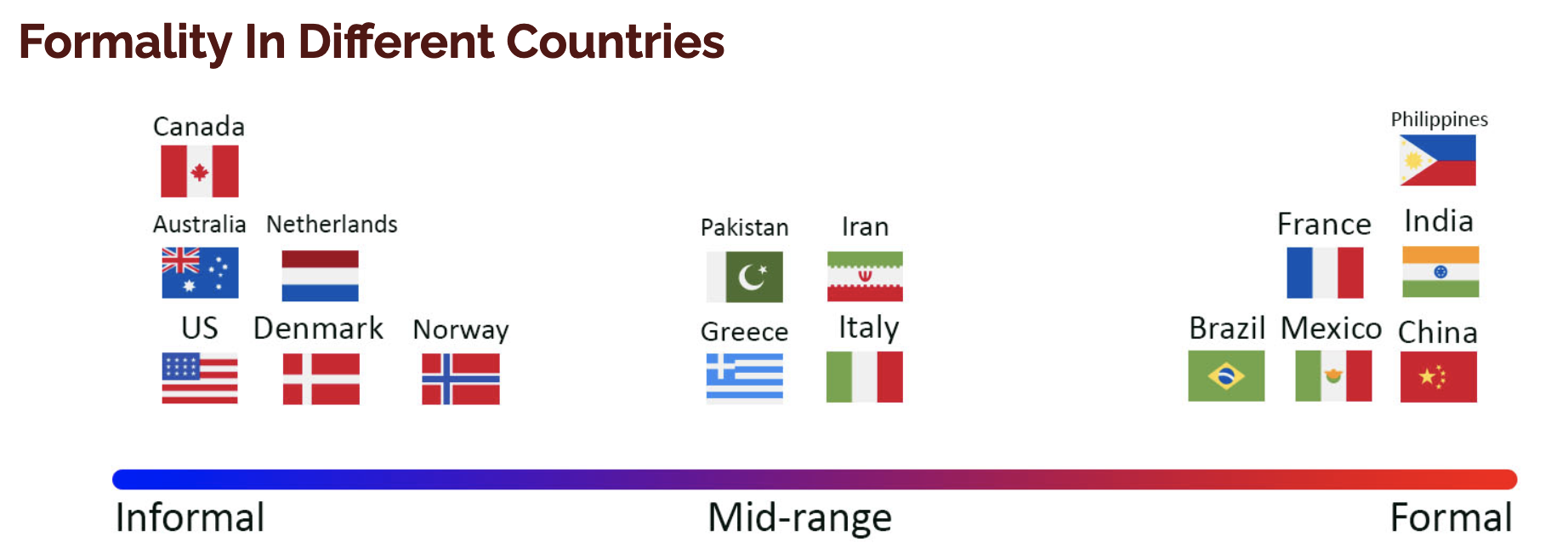

- Formality

- Let’s now explore the differences between formal and informal communication styles, which is another important category in cross-cultural communication.

- Formality refers to the extent to which communication is governed by specific conventions around the forms of address, appropriateness of topic, and so on.

- Recall the distinction between high-power distance (hierarchical) and low-power distance (egalitarian) cultures. This distinction provides a helpful cue to indicate the formality of a communication style in a particular culture.

- Hierarchical cultures value formal communication with proper style and protocol, especially during interactions with superiors.

- Egalitarian cultures favour informal communication style that deemphasizes the markers of power differentials between the speakers even in interactions with superiors.

- The following image shows where countries fall on the formality scale. As always, remember that all cultural values exist on a continuum, so there will be variation even within countries which appear to be in the same area on the scale and within individuals in each country.

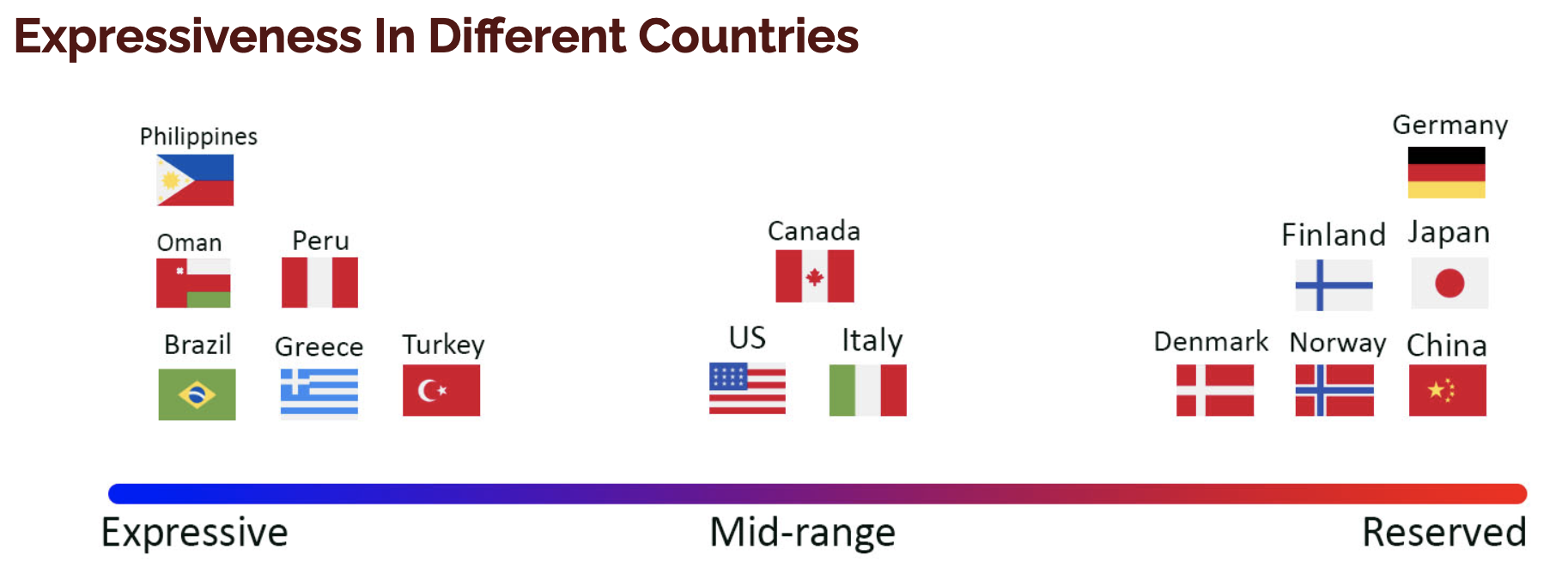

- Expressiveness

- The next important category of intercultural communication relates to the degree of emotion and energy that people are expected to show when communicating. Based on this characteristic, cultures can be positioned along the continuum from expressive/enthusiastic to reserved.

- By way of illustration, Canada and the U.S. are considered to have expressive communication styles but Americans generally exert more emotion and energy when speaking than Canadians.

- Therefore, Americans generally tend to have a more expressive communication style compared to Canadians. This difference was noted by former President Barack Obama, who remarked in his 2016 speech welcoming the Canadian Prime Minister to the U.S.: “Our Canadian friends can be more reserved, more easygoing. We Americans can be a little louder, more boisterous..”

- With regards to expressive communication styles, Mediterranean, Arab, and Latin American cultures are known for their expressive and warm communication styles. People tend to speak loudly, passionately, and use animated gestures.

- In contrast, cultures that favour reserved communication tend to favour calm and matter-of-fact communication styles dissociated from emotional reactions.

- The following image shows where countries fall on the expressiveness scale. As always, remember that all cultural values exist on a continuum, so there will be variation even within countries which appear to be in the same area on the scale and within individuals in each country.

- Greetings

- Greetings are defined as “patterned routines that facilitate social relations” (Spencer-Oatey, 2018, p. 303). Different cultures use different forms of greetings that have different meanings associated with them.

- These various forms of greetings used in Canada, the UK, and China show that there is a range of formulaic phrases that are used in different cultures to greet others. A Canadian who is greeted by the British greeting, “Are you all right?” might interpret it as a sign of concern and start wondering if they look tired or sick.

- Greetings used in China, such as “Have you eaten yet?” might also confuse those who are unfamiliar with the culture.

- It takes take time to adjust to an unfamiliar form of greeting and how to respond in culturally appropriate ways. While in Canada and the U.S. a short and positive response to the standard “How are you?” is expected, in other cultures it is appropriate to respond in a less positive way (e.g., “just so-so”), share challenges, or even complain.

- In order to perform greetings in culturally appropriate ways, it is important to know not only the formulaic phrases used as greetings but also expected responses (what to say and how to say it). A person must practice culturally specific greetings for some time before one starts feeling more at ease and natural when greeting others in another country.

- Non-verbal behaviours associated with greetings also vary across cultures. In many collectivistic cultures, greetings are often accompanied by physical contact, such as hugs, handshakes, or kisses on the cheek. The nature of relationships between conversational partners and the context also determine the appropriate greeting behaviour.

- Small Talk

- How often do you engage in small talk in your workplace? What are your favourite conversation starters? In the Canadian workplace, we frequently engage in small talk with colleagues either before a meeting or throughout the workday.

- Communication research tells us that small talk plays an important role in building and maintaining working relationships with colleagues and managers. Small talk is not simply chatting about uncontroversial topics such as the weather or commute to work.

- Casual conversations with colleagues often lead to meaningful exchanges and deepen our working relationships. To put it simply, small talk serves as a relational bridge in our professional and social lives.

- In some countries, small talk is an essential precursor to business relationships and precedes business meetings.

- So what strategies can you use to be more effective intercultural communicator? First, keep in mind that people receive and send messages differently depending on their cultural background. Be aware of your cultural assumptions and associations and know your own communication style. Second, try to understand the communication rules by which your conversation partner is playing. Look for differences in context, directness, formality, expressiveness, and politeness. Third, assume positive intentions. If someone says something that makes you feel uncomfortable or frustrated, give them the benefit of the doubt. Don’t jump to the conclusion that they had negative intentions. Most likely, it was a miscommunication or misinterpretation. Fourth, adjust your communication style when necessary. If you are in a culture that values formality, use more formal communication style when addressing people and talking to them. If you’re a native speaker talking to a non-native speaking colleague, speak slower, not louder. Use active listening by summarizing prior information or asking for clarification. Say things in more than one way and use different vocabulary.

Unit 4 Summary

Many intercultural experiences centre around communication and as such, being able to recognize and interpret communication style differences is a key cultural skill. In this unit we introduced 4 of these differences.

First, some cultures rely more heavily on context than others which affects how much information needs to be actually stated and how much can be assumed. Second, some cultures are comfortable stating what they mean explicitly, and directly, while other cultures place great importance on how something is stated, preferring to indirectly communicate certain messages. Interestingly, this does not always correlate with how that culture prefers to provide negative feedback – sometimes a culture that is quite direct for all other forms of communication will be quite indirect when it comes to criticizing someone’s work. Third, some cultures communicate quite formally with specific, even complex customs around proper style and protocol, while others are more relaxed and informal. Finally, some cultures communicate expressively with emotion and movement while others are more reserved.

Each of these differences can lead to significant misunderstandings if the two parties communicating don’t recognize what is happening. Someone from a low context culture may feel like someone from a high context culture is hiding information and being purposely evasive. Someone from an informal culture may perceive someone from a formal culture as stuck up or too picky about small matters. And so on. But as we learned in Unit 3 about cultural values, when we understand what is happening below the surface, it is easier to be empathetic and to find ways to communicate more effectively.

In addition to these larger communication differences, there are lots of little differences in things like greetings and small talk, all of which can add up over time. There is no way to learn every possible difference and keep them in mind all the time. Instead, work to be aware of your own assumptions, recognize (and try to understand) that your conversation partner might have different assumptions from you. Be willing to give them the benefit of the doubt, adjust your own style, and ask questions to improve the effectiveness of your communication.

Unit 5: Cultural Differences in Non-Verbal Communication

If you work across cultures, you need to be aware of cultural differences in gestures, personal space, body language, touch, eye contact, and other aspects of non-verbal communication.

Intercultural skills you will develop in this unit include:

- Developing an awareness of common differences in non-verbal communication across cultures.

- Recognizing common cultural misunderstandings based on differences in non-verbal communication.

- Culture Influences Non-Verbal Communication

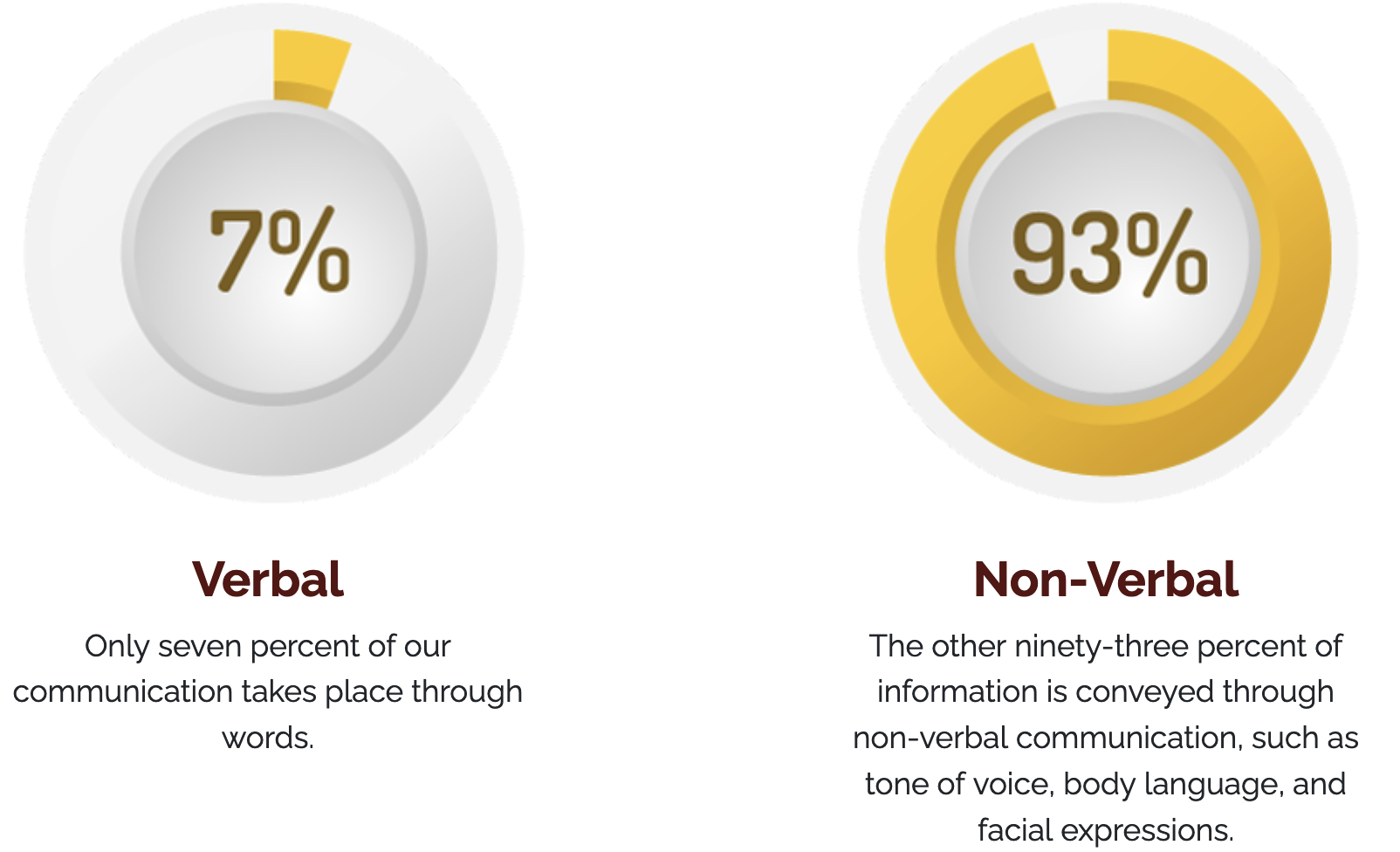

- We will now briefly explore cultural differences in non-verbal communication focusing on the most important differences that are important to keep in mind for good interpersonal communication. These differences include personal space, body language, silence, smiles, touching, dress and appearance, as well as colours and numbers. As you may already know, most of our communication is non-verbal.

- Similar to verbal communication, non-verbal communication is influenced by cultural factors. The same gestures and facial expressions can mean different things in different countries.

- We will now briefly explore cultural differences in non-verbal communication focusing on the most important differences that are important to keep in mind for good interpersonal communication. These differences include personal space, body language, silence, smiles, touching, dress and appearance, as well as colours and numbers. As you may already know, most of our communication is non-verbal.

- Space and Touch

- Personal Space

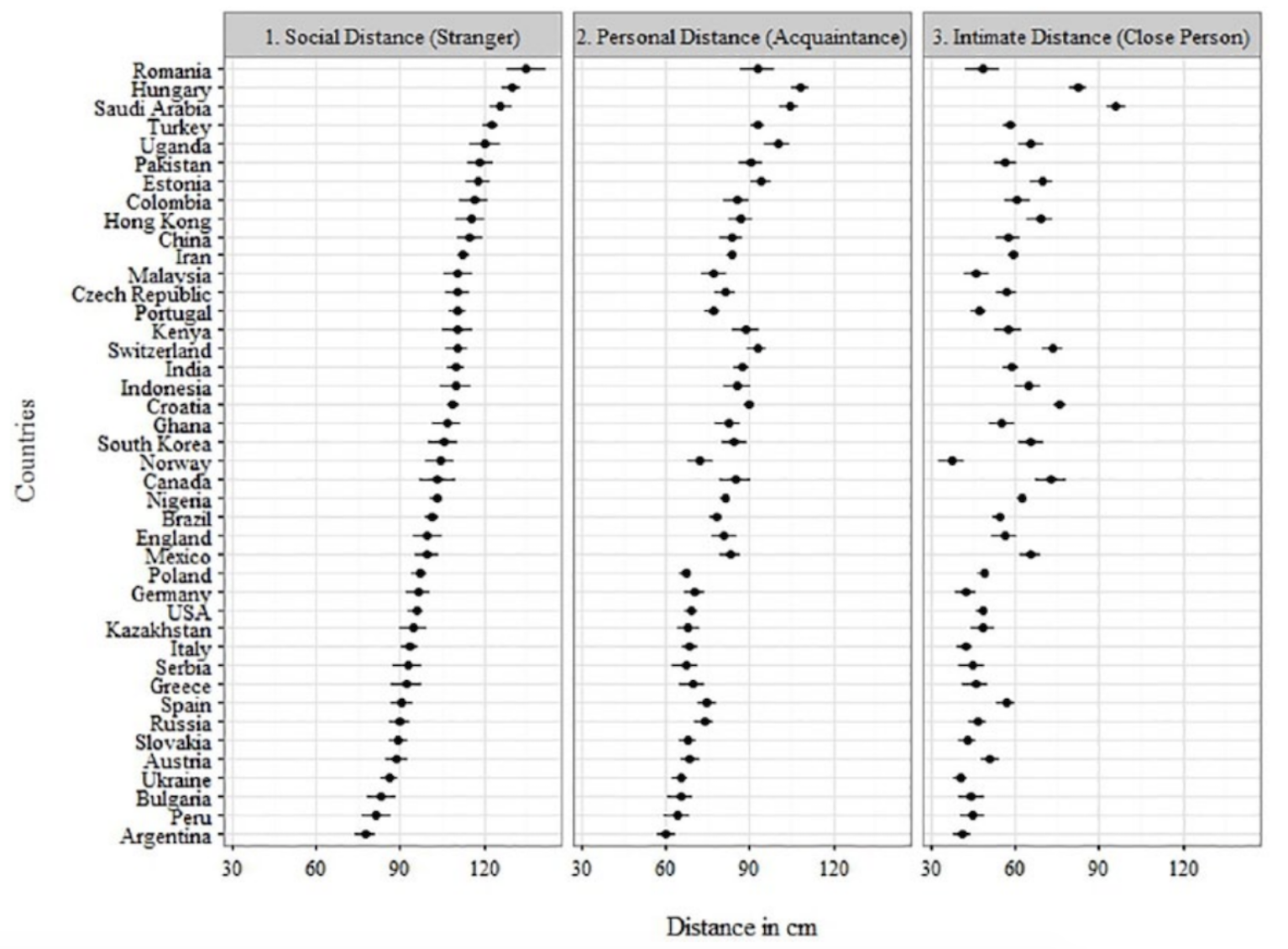

- We will start our discussion by exploring the concept of personal space. In the 1960s, American anthropologist Edward T. Hall was the first to study and analyze the use of personal space across cultures. The basic premise of Hall’s work was that each of us had a desired amount of personal space, and this amount would depend to a large degree on our cultural background. As a rule of thumb, people in:

- Individualistic Cultures: prefer a larger personal space.

- Collectivistic Cultures: are much more comfortable with less personal space.

- Think about your personal space. When talking to someone at work, how much space do you prefer to have between you and the person you are talking to? How do you respond when someone moves closer than what you are comfortable with?

- According to cultural research, most Canadians and Americans prefer to stand, or sit, one and a half to two feet away. However, if you keep this distance when talking to a Japanese or Australian, you might unintentionally make them uncomfortable because Japanese and Australians prefer even larger personal distance (three or four feet away).

- On the other hand, if your colleagues or friends are from Brazil, Mexico, or the Middle Eastern countries, you might notice that they like to be much closer when talking. Maintaining too much distance during conversation might be perceived as aloofness and unapproachability. This is because in these cultures there are different rules governing personal space and people are comfortable being less than an arm’s length away. These cultures also tend to use touch a lot more than North Americans.

- The following table shows the results of a study on how personal space preferences vary around the world.

- We will start our discussion by exploring the concept of personal space. In the 1960s, American anthropologist Edward T. Hall was the first to study and analyze the use of personal space across cultures. The basic premise of Hall’s work was that each of us had a desired amount of personal space, and this amount would depend to a large degree on our cultural background. As a rule of thumb, people in:

- Touching

- Related to personal space is the use of touching. Cultures vary in the extent to which they use touching, hugging, and kissing when greeting someone or conversing.

- Frequent touching of an arm, elbow, or shoulder during a conversation is common in most Latin American and Mediterranean countries, which are considered high-contact or high-touch countries.

- Keep in mind that in some cultures, public touching, hand-holding, and public displays of affection are prohibited. For example, public touching is allowed only between same-sex persons. In the United Arab Emirates and Saudi Arabia, the law prohibits physical contact in public between members of the opposite sex.

- One of the cultural habits that often confuses Canadians who travel to the Middle East, India, or Pakistan is a cultural habit of hand-holding among males that is common in these countries. Canadians are surprised to find that, in these countries, hand-holding is used as a sign of close friendship and respect among males. This photo of President Bush and Crown Prince Abdullah of Saudi Arabia is an excellent example of the cultural habit of hand-holding that is common in Arab cultures.

- Related to personal space is the use of touching. Cultures vary in the extent to which they use touching, hugging, and kissing when greeting someone or conversing.

- Personal Space

- Facial Expressions

- Eye Contact

- We generally associate eye contact or a lack of it with attentiveness and interest or inattention and lack of interest. However, there are implicit cultural rules that govern eye contact, especially in situations with asymmetrical power relationships (e.g., manager-employee).

- We learn what constitutes appropriate eye contact from the way we are socialized as children.

- In the images below, both sets of children are being completely respectful within their cultural context. Imagine, however, that a child from one class joined the other class – their eye contact or lack thereof would likely be considered disrespectful.

- Individualistic Cultures: children make eye contact with their teacher.

- Collectivistic Cultures: children avoid eye contact with their teacher.

- In Canada and the U.S., direct eye contact communicates that one is interested and attentive. Therefore, during conversations and meetings, speakers and listeners are expected to maintain eye contact when communicating. North Americans perceive someone who avoids eye contact as inattentive, unfriendly, and untrustworthy. Interestingly, in Canada and the U.S. it is important to maintain eye contact in conversation but it is also important to not fully lock eyes. Conversational partners are expected to periodically break eye contact.

- Compare this to the Middle East, where continuous eye contact during the conversation is very important. If you glance away, the person you are talking to might be offended because they would think that you are uninterested in the conversation. Staring is another interesting example of non-verbal behaviour. In North America, it is rude to stare at someone. However, in many countries staring is considered acceptable.

- In contrast to direct eye contact expected in North America, in Asian and African cultures an avoidance of direct eye contact is a sign of respect and politeness. In collectivistic cultures, direct eye contact indicates that the person is disrespectful, aggressive and untrustworthy. In many cultures, children are taught early on to lower their eyes when speaking to a superior. Looking away is a sign of careful attention rather than disinterest and staring at a person of higher status is considered rude.

- Smiling

- Smiling is another important aspect of non-verbal communication since smiling is a basic facial expression found in all cultures.

- Even though a smile universally means joy and happiness, there are cultural variations in when, and how frequently, people smile.

- When you travel overseas, you might notice that, in many countries, people generally don’t smile at strangers and tend to smile a lot less often than Canadians or Americans.

- In France and Russia, for instance, it is not common to smile at strangers. This cultural difference in smiling at strangers often leads to the North American misperception of the French and Russians as unfriendly.

- In Asian cultures, smiling may be used to express joy, but it can also be used to hide embarrassment, anger, or sadness. As an example, if a taxi driver or a waiter in Thailand made a mistake, they will likely smile to hide embarrassment.

- Therefore, knowing that a smile can have multiple meanings across cultures is useful in accurately interpreting cross-cultural situations.

- Eye Contact

- Body Language

- Silence

- The meaning of silence across cultures is another important factor to consider in intercultural communication. Silence may mean:

- Agreement, disagreement, reflection on what is said, respect

- If you are giving a presentation to an audience in North America, you can expect questions and comments after your presentation.

- However, in Asia you might be surprised to find out that there is complete silence after your talk. This is because Asian cultures value silence and use it a lot more often than North Americans, who tend to feel uncomfortable with silence when interacting.

- The meaning of silence across cultures is another important factor to consider in intercultural communication. Silence may mean:

- Gestures

- Another fascinating area of cultural differences in non-verbal communication has to do with gestures. The same hand gesture may have different meaning across cultures.

- Let’s imagine you are having dinner with several different international executives. The waiter asks you if the food was okay and you give an “Okay” sign to tell them that the meal was great.

- There is a famous historical example of improper use of the OK gesture. In the 1950s, when Richard Nixon arrived in Brazil, he gave the “OK” sign to the media and the people of Brazil, only to learn later that this gesture is the Brazilian equivalent of giving the middle finger in America. A little cross-cultural training could’ve helped him to avoid this embarrassing situation.

- Three additional examples of gestures that may be interpreted differently across cultures include:

- In many cultures, a ‘thumbs up’ sign signals approval but in other cultures (such as in the Middle East) it is an insult, similar to what raising a middle finger means here in Canada.

- In many cultures, nodding up and down indicates agreement or acceptance, but in other countries (such as Greece, Turkey, and Bulgaria), it actually indicates refusal, or ‘no’.

- In many cultures, a head shake (left and right) indicates refusal or disagreement, but in some countries (such as Bulgaria and Albania), it actually means ‘yes’.

- Silence

- Physical Appearance

- Dress and Appearance

- Dress and appearance is another important aspect of cross-cultural communication.

- Fashion Quality: If you work in Latin American or in European countries, you should be aware that appearances matter and you might be judged based on how you look. In Europe and Latin America, people generally tend to be more fashion conscious than North Americans. Dressing well and wearing high-quality pieces is important since clothes indicate social standing and success. As a result, people put a lot of thought into how they look and how they dress.

- Workplace Attire: There are also cultural variations in terms of what is considered appropriate workplace attire. For example, in Latin American countries many women wear brightly coloured business attire. In Asia and the Middle East, women are expected to wear neutral colours. In some countries, women can’t wear pants to the office.

- Scent & Makeup: There are also different cultural norms for what is considered acceptable in the workplace as far as make-up and perfume use . While in Canada too much of either is inappropriate (and many workplaces are completely fragrance-free), in many countries it is considered acceptable to wear light (or bold) scent and makeup in professional settings. Interestingly, the preferences for fragrances are also heavily influenced by culture – yes, “smelling good” means different things around the world! (Montell, 2020).

- If you plan to work overseas, it is always a good idea to find out what qualifies as business formal and business casual attire, and what is appropriate to wear for work-related social outings. This article outlines Business Clothing Etiquette Around the World.

- Numbers & Colours

- Another interesting area of non-verbal communication has to do with the meanings different cultures give to numbers and colours. Professor Svitlana explains: “In many cultures, certain numbers have special significance. Consider the following scenario: a North American company that manufactures golf balls expands its market to Japan and China. The company plans to sell the standard package of 4 golf balls to the local customers. Do you think this is a good idea? Well, if the company had done cultural research on their target market, they would’ve found out that number 4 is considered unlucky in Japan and China and is avoided by most people. If you were in an elevator in China, you would see that, along with number 13, numbers 4 and 14 are missing. The reason is that in China, Japan, Korea, Vietnam, and Hong Kong, number 4 is considered unlucky because “four” is pronounced the same way as “death”. As a result, the number 4 is omitted in license plates, phone numbers, and building floors. Some foreigners who live in China report that they are able to rent cheap apartments and offices located on the fourth floor. On the other hand, 8 is considered particularly lucky in China. A wealthy Hong Kong businessman paid five million dollars for car registration number eight. Even when scheduling events such as weddings, locals pay attention to the date of the event. For example, the opening ceremony for the Beijing Olympics took place at 8 p.m. on the eighth day of the eighth month in 2008. Another interesting difference related to numbers has to do with the meaning attached to even and uneven numbers in some cultures. For instance, in Russia and Ukraine, it is inappropriate to bring a bouquet of flowers that has an even number of flowers. An even number of flowers is appropriate only at funerals. When it comes to colours, keep in mind that colours have different meanings in different cultures. If you are designing a website, marketing materials, or a presentation for an audience from a specific country, consult one of the colour symbolism charts available online. Red, for example, has positive associations in many cultures.”

- Dress and Appearance

Unit 5 Summary

This concludes our discussion of cultural differences in non-verbal communication. As you can see, there are a lot of cultural variations! What can you do to become more aware of cultural differences in non-verbal communication? Occasional cultural blunders are inevitable when working overseas or working with people from various cultural backgrounds. However, with a little research and awareness of common cultural differences in non-verbal norms and rules, you can be better prepared to deal with possible misunderstandings.

When cultural differences are at play, pay special attention to non-verbal messages, such as tone of voice, body language, and facial expressions used by your conversation partner.

Prior to travelling overseas, learn about the cultural customs related to non-verbal communication in your destination country. A good place to start is to learn about the meaning of eye contact, personal distance, common gestures, dress code, and acceptable forms of greeting, such as a handshake, kiss, or bow. If you have business cards, find out what’s the protocol for accepting and presenting business cards.

Spending some time on researching the culture can help you avoid cultural mistakes and will go a long way in demonstrating cultural sensitivity. Not to mention that learning what gestures, smiles, colours, and numbers mean in different parts of the world is really fascinating.