Intellectual Property

IP law grants creators exclusive rights over their creations. These rights prohibit others from making, selling or using their creation without the owners’ permission. IP law also dictates limited ways in which other creators can build on existing works to create new works. Thus, IP law also aims to stimulate the creation of derivative works that extend, adapt, or draw inspiration from existing works.

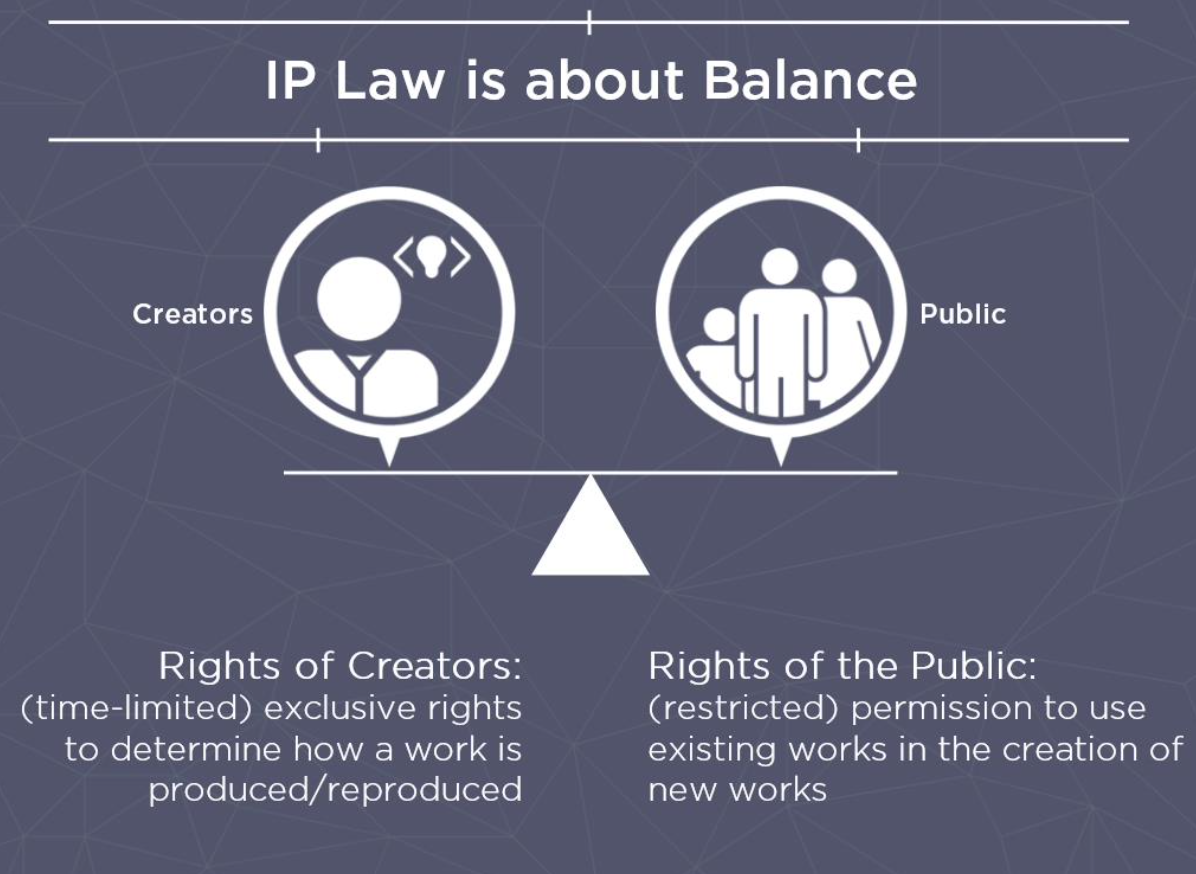

IP law is about balance. It gives creators exclusive, limited-time rights to determine how their works are produced and reproduced.

This action, in turn, gives creators an incentive to create innovative works that enrich society.

It also gives the public and other creators some flexibility (through time limits and through fair-use exclusions) to create new works that are derived from existing works.

In this manner, IP law attempts to balance the rights of all parties, so that the incentive for all parties is to create innovative works.

If you or your company develops and sells products, if you invent solutions, if you create original works, then you are creating IP.

At its heart, IP law protects creators’ rights to produce and reproduce their original works. It gives them time-limited, exclusive rights to control how their works are reproduced and sold, or licensed, to consumers.

How Does IP Law Apply to Software?

“Software is deemed a literary work that is protected by copyright”. As well, a program’s user interface is deemed an artistic work, in terms of its graphics and its audio, so is protected by copyright.

However, software is not like other creative works, in that the essence of its value is not in its expression. The primary value of software arises from its functionality. Unfortunately, copyright protects only the expression of functionality (how it is encoded in source code). Copyright does not protect the functionality itself.

The appropriateness of copyright for software becomes even more questionable when considering how software and hardware are fundamentally interchangeable. Any software design could instead be implemented as hardware, for example, by building a special-purpose computer with the desired functionality hardwired into it. Then, the work would be considered a machine and its IP protected under patent law.

Can Patent Law Protect The IP in Software?

Maybe…

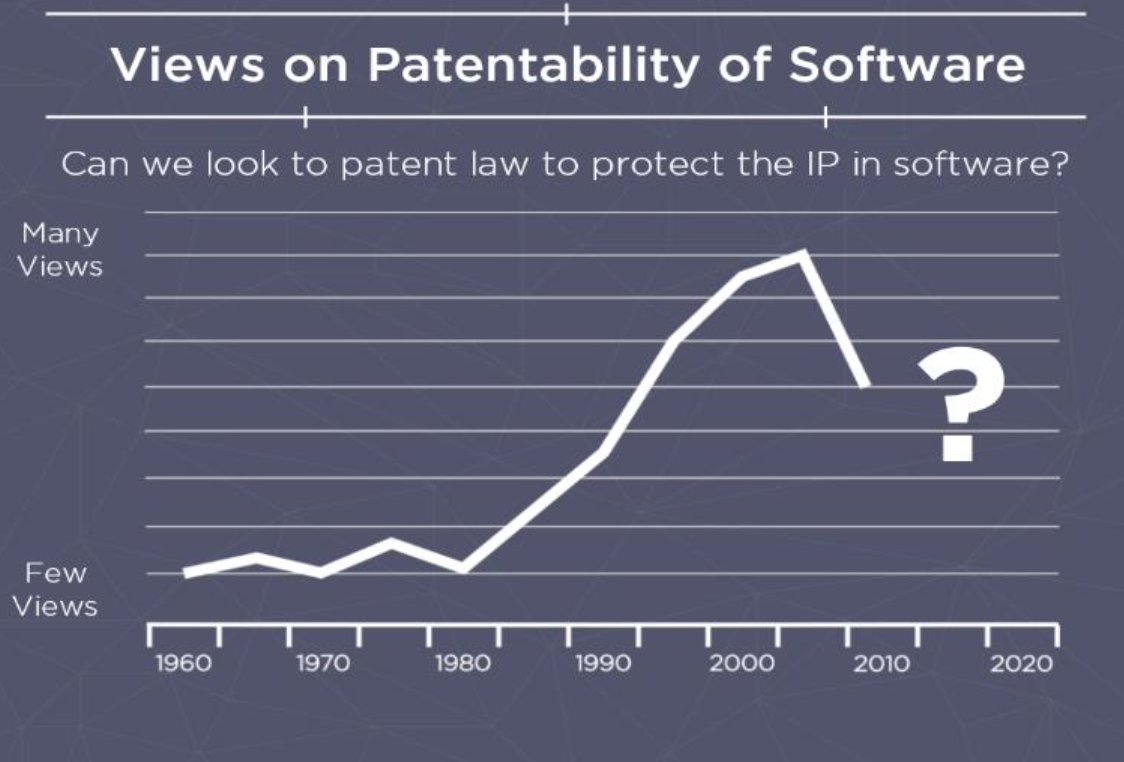

In the early days of software, there was little to no consideration of patenting software. Patents cannot protect “abstract ideas or mathematical formulae” and software and algorithms were considered exactly that.

Although software by itself was not necessarily patentable, if the software interacted with another element of the invention (such as a machine or a non- software process), such that the invention as a whole performed a function that could be patented, then the software component could also be patented.

Thereafter, companies claimed patentability of software by tying the software to a physical component or platform (such as the hardware process or, or the data store) or by tying the software to a larger manufacturing or business process. For example, there are a number of software patents related to financial processes.

More recently, courts have started to revert to viewing software programs as abstract algorithms and abstract ideas, especially when the accompanying physical component is a general-purpose computer rather than some special-purpose hardware device.

Thus, current views on the patentability of software are mixed, and as a result, court rulings involving software patents can be unpredictable.

These days, the software industry relies heavily on copyright protection. Copyright protects against the literal copying of a program’s source code and its interface.

”Interestingly, protection against non-literal copying is being extended to other literary works, such as novels, plays, and films. Thus, copying need not be verbatim to be considered copyright infringement. Infringement includes creating imitations that are “strikingly similar” to an original copyrighted work.” For example, infringement could include stories or scripts that have strikingly similar settings, plot lines, and characters.

However, IP law does not give creators absolute control over their creations. There are means by which you, and others, can legally use existing works in your own work and in your own creations so that neither you nor your employer is vulnerable to lawsuits for copyright infringement.

Derivative Work

A derivative work is a new creation that makes use of existing works. Derivative works include novel and useful improvements on inventions. Music recordings or videos that include samples of other songs or videos are derivative works.

Another example would be an innovative interpretation of an existing work, such as an innovative cover of a song, or a modern-day interpretation of classical literature, or a parody of an existing performance art.

A derivative work is any creation that includes elements from one or more pre-existing works, each of which might have its own IP protection. The existing works might be used as is or might be adapted.