Colonialism and Sovereignties of Law

Sovereignty

What is sovereignty? Sovereignty is the supreme authority within a territory.

Sovereignty is dependent on a state. Sovereignty concerns holding authority over a territory (land). Therefore, as a legal concept, it minimizes the difference between the political concept of the state and the law.

The Crown asserted sovereignty over the territory that is now the Canadian state by securing legal entitlement through “raw assertion” (Borrows 1999). This meant that the Crown proclaimed itself as the sovereign (supreme authority) over this land by no means other than to assert it. There was no preceding right or authority that granted the Crown this sovereignty. Rather, sovereignty was seized.

Crown title, in other words Crown ownership, is an anathema to Indigenous groups and Indigenous relationships to land and ownership. But by asserting supreme authority over all Indigenous-occupied territories, the sovereignty claimed by the British Crown established, or mandated, a “feudal relationship” centred on the use of land. Acts of Sovereignty, the laws that consolidated Crown sovereignty in what is now Canada, were focused on stripping away Indigenous Peoples’ access to, and relationship with, the land.

Acts of Sovereignty

In order to secure sovereignty over what is now Canada, the British Crown created the constitutional British North America Act of 1867. Further acts of sovereignty, which began with the Royal Proclamation of 1763 (which will be detailed on the next content page) included acts that created a legal status of “Indian”. The creation of a legal status of “Indian” subjugated Indigenous people under British law. Through these British “acts of sovereignty” Indigenous people lost their own soveriegnty, and were treated as subjects requiring assimilation. Attempts to assimilate Indigenous people into British, now Canadian, law involved the attempted annihilation of Indigenous identities, cultures, and traditions.

In 1876, the Indian Act consolidated the laws concerning the legal status of Indigenous people under British sovereignty. From 1876 to 1961, the Indian Act legitimated the removal of land, culture, traditions, and identity from persons who lived on the land that the Crown (British, and French initially in Quebec) claimed as their own.

The Indian Act is still law in Canada today. It has been significantly amended, notably in 1951 and 1985. Authors such as Bonita Lawrence and Brenna Bhandar have written about the gendered nature of the Indian Act. The colonial state attempted to “break the relationships of [I]ndigenous [P]eoples to their land” (Bhandar 2016) by privatizing land and denying women the ability to keep their Indian status, including their ability to live on the land, if they married a non-status male.

Due to the activism of Indigenous women fighting against gender-based discrimination in the Indian Act, case law since the 1960s has highlighted the gender discrimination embedded in the Indian Act. Following the amendments of the Indian Act of 1985, the Act ostensibly addressed gender discrimination to align the act with the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms.

Nevertheless, up until 2017, the Indian Act continued to discriminate against women, tying women’s status entirely to their husband and preventing women—based on a series of factors—from passing down Indian status (see Parrott 2022).

As noted above, the Indian Act has not been abolished. Ongoing complications between Indian status and Band status (Assembly of First Nations 2019), the latter potentially continuing gender-based discrimination despite the case law noted above, characterize the fraught reality of this settler-colonial law. Proposals for self-governance, including successful agreements such as the James Bay and Northern Quebec Agreement in 1984, and Supreme Court of Canada case law have acknowledged constitutional rights of certain Indigenous groups and treaties under section 35 of the Canadian Constitutional Act of 1982. Nevertheless, sovereignty in Canada persists as a colonial tool that lays claim over Indigenous people, erasing any prior claims to sovereignty (pre-Crown) or Indigenous laws and legal traditions.

The Rule of Law

Sovereignty works in tandem with a second foundational legal principle: the rule of law.

The rule of law claims that law is supreme over government and private individuals. It exists as a foundational principle to preclude arbitrary power. In other words, the rule of law is what prevents leaders from acting as if they were “above the law.” The rule of law also refers to the procedural rules that order the hierarchy of the law. If you recall our discussion of legal positivism, this is precisely a positivist tool of law. For instance, that the Supreme Court of Canada and the Charter of Rights and Freedoms is binding on all levels of law and courts throughout Canada. In Canada, the rule of law is affirmed in the preamble to the Canadian Constitution, 1982.

But what about colonial acts of sovereign assertion? Was seizing sovereignty over Indigenous-occupied land not an archetypal exercise of arbitrary power?

John Borrows, a professor of law and Canada Research Chair of Indigenous Law at the University of Victoria, explores how the Crown’s raw assertion of sovereignty denied any power to Aboriginal governance. By claiming sovereignty on the land that is now Canada, the Crown “started the clock” of history and began law—including the rule of law—after claiming supreme authority. Thus, the Crown was not subjected to its own rule of law because it created the law by claiming sovereignty. The raw assertion of sovereignty also erased any possibility for Indigenous law and legal tradition to be recognized as equal to the settler-colonial, British/Canadian law.

The rule of law working in tandem with sovereignty is illustrated in an 1888 case concerning land, which is highlighted in the reading Borrows (1999, 562):

[T]he tenure of the Indians was a personal and usufructuary right, dependent upon the good will of the Sovereign. The lands reserved are expressly stated to be “parts of Our dominions and territories” . . . It appears . . . to be sufficient for the purposes of this case that there has been all along vested in the Crown a substantial and paramount estate, underlying the Indian title, which became a plenum dominium whenever that title was surrendered or otherwise extinguished.

- St. Catherine’s Milling and Lumber Co. v. R. [1888] 14 App. Cas. 46 at 54–55 (P.C.)

plenum dominium

full ownership combining both title and exclusive use (from Roman and civil law)

In settler-colonial Canadian law, the rule of law applies to everything that is subjected under the Crown. This is how the Crown can hold the title to the land without having to prove it: mere assertion is enough (Borrows 1999, 573). “Indigenous title” is different to “Indigenous right”: Both are subjected to the law, but title must be proved. There is no inherent right to Indigenous title.

Case law in the Supreme Court of Canada, discussed below, recognized the right to Aboriginal land title, but simultaneously created tests to allow justifiable infringement of Aboriginal rights.

What do you thinking? Does the one who controls the language of law exist above the law?

Canadian Constitution Act of 1982 and Supreme Court of Canada Case Law

A series of cases trace the debates concerning land rights and treaty rights. These are distinct legal matters, different from legal questions of Indian status concerning the Indian Act. Both legal questions of “Indian status” and “Aboriginal rights” remain contested in provincial and federal courts. Political debates are also ongoing amongst Indigenous people and settler Canadians. You are encouraged to explore the further listening, further reading, and further watching resources provided in this week’s content to familiarize yourself with these debates.

Indigenous rights, contested in the case law and statute discussed below, include access to ancestral lands and resources and the right to self-government.

Calder v. British Columbia A.G.

The question that was presented in the Calder case, brought to the Supreme Court by Frank Calder, concerned whether the Nisga’a were in possession of their land since “time immemorial.” This was an important question because the Royal Proclamation of 1763 acknowledged that Aboriginal legal title existed and declared that only the Crown can buy land from First Nations:

And whereas it is just and reasonable, and essential to our Interest, and the Security of our Colonies, that the several Nations or Tribes of Indians with whom We are connected, and who live under our Protection, should not be molested or disturbed in the Possession of such Parts of Our Dominions and Territories as, not having been ceded to or purchased by Us, are reserved to them, or any of them, as their Hunting Grounds . . .

And We do further declare it to be Our Royal Will and Pleasure, for the present as aforesaid, to reserve under our Sovereignty, Protection, and Dominion, for the use of the said Indians, all the Lands and Territories not included within the Limits of Our said Three new Governments, or within the Limits of the Territory granted to the Hudson’s Bay Company, as also all the Lands and Territories lying to the Westward of the Sources of the Rivers which fall into the Sea from the West and North West as aforesaid …

And We do hereby strictly forbid, on Pain of our Displeasure, all our loving Subjects from making any Purchases or Settlements whatever, or taking Possession of any of the Lands above reserved, without our especial leave and Licence for that Purpose first obtained. ----- (Royal Proclamation, King George III of England, 7 October 1763, reprinted in RSC 1985, App II, No. 1.)

Calder was successful in his claim: The Supreme Court ruled the Nisga’a had pre-existing title to their lands based on occupancy and use.

Canadian Constitution Act of 1982, Section 35

Section 35 of the Constitution Act affirmed the Royal Proclamation of 1763 in modern Canadian constitutional law. This section (35) protects a broad scope of Indigenous and treaty rights. However as with all statute, the application of this law needed to be tested in the courts to define the parameters of Indigenous or Aboriginal rights and treaty rights.

Rights of the Aboriginal Peoples of Canada

35. (1) The existing Aboriginal and treaty rights of the Aboriginal Peoples of Canada are hereby recognized and affirmed.

(3) For greater certainty, in subsection (1) “treaty rights” includes rights that now exist by way of land claims agreements or may be so acquired. Aboriginal and treaty rights are guaranteed equally to both sexes.

R. v. Sparrow [1990] 1 SCR 1075

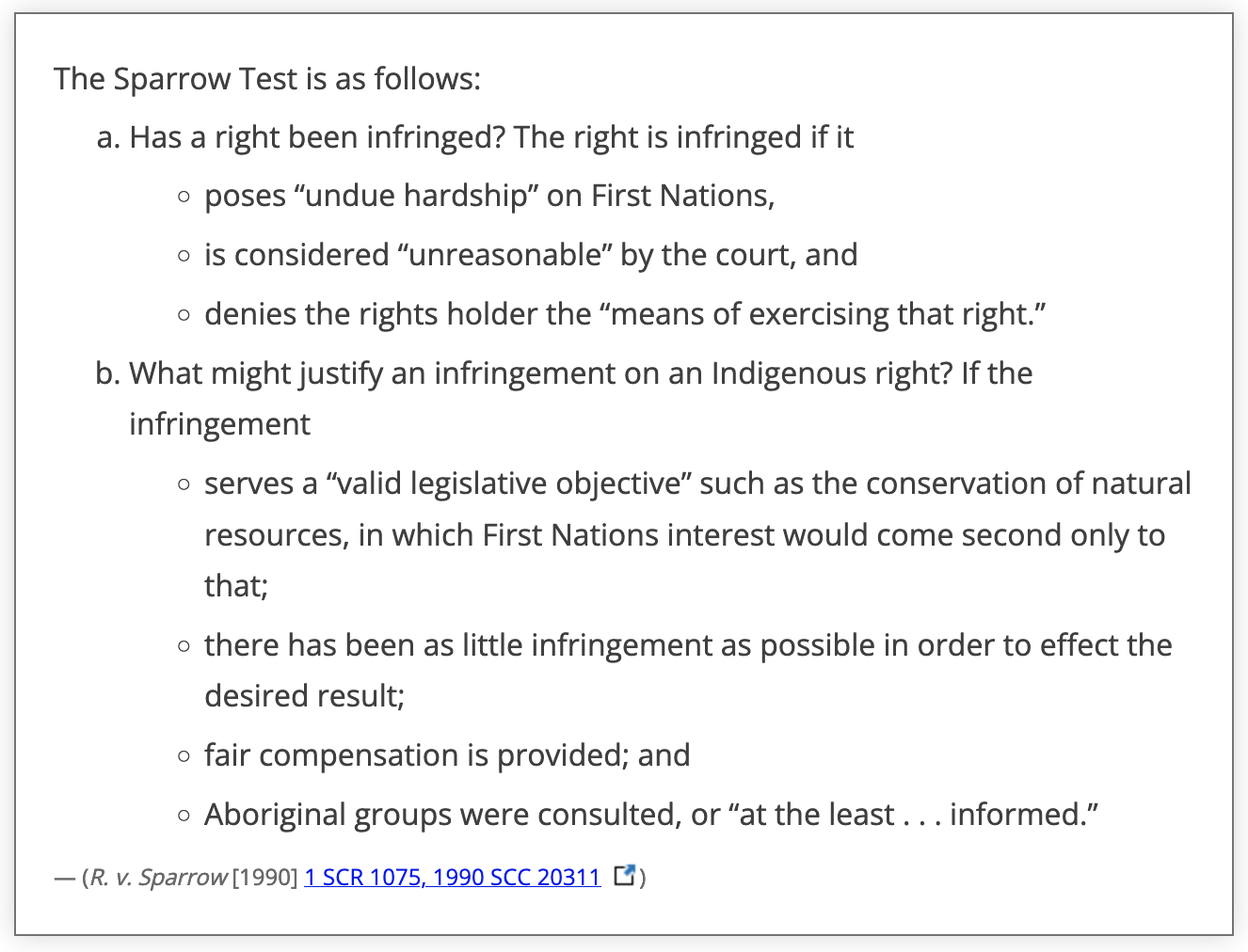

Sparrow was the first Supreme Court of Canada case to test section 35 of the Constitution Act, 1982. Ronald Sparrow, a Musqueam man in British Columbia, was caught fishing contrary to section 61 (1) of the Canadian Fisheries Act. He was charged and arrested. In his defence, Sparrow argued that the right to fish was an immemorial right guaranteed under section 35. He asserted his Musqueam fishing rights as per the Constitution Act of 1982, Section 35 (1).

The Supreme Court of Canada ruled in Sparrow’s favour, finding that Aboriginal rights were legitimate “existing” and “inherent” rights when fishing for food, social, and ceremonial purposes (R. v. Sparrow). The case established the Sparrow Test to interpret section 35.

Delgamuukw v. The Queen [1997] 3 SCR 1010

This landmark Supreme Court case of Delgamuukw culminated in 1997 after over ten years of litigation and community organizing by the Gitxsan and Wet’suwet’en nations. Delgamuukw v. British Columbia successfully affirmed exclusive right to traditional territory for the Gitxsan and Wet’suwet’en Houses. However, the process of proving this right was drawn out and illustrated the extent to which Canadian law remains a colonial “white man” law.

if we don't have a history, and we don't have a language, and we don't have a sacred homeland, and we don't have our own spirituality, then we must not be a people, so we must be invisible — so we’re invisible people.

Chief Yagalahl Dora Wilson, quoted in Forester 2020

In Delgamuukw, for the first time in its history, the Supreme Court of Canada admitted oral histories as evidence. This meant that songs and stories told through the generations by Elders were granted legal status as evidence of a continual connection to the land held by the Wet’suwet’en and Gitxsan Houses. This was in lieu of the Gitxsan or Wet’suwet’en having to provide British/colonial style documents in order to prove property ownership and use.

At trial, the appellants’ claim was based on their historical use and “ownership” of one or more of the territories. In addition, the Gitksan Houses have an “adaawk,” which is a collection of sacred oral tradition about their ancestors, histories, and territories. The Wet’suwet’en each have a “kungax,” which is a spiritual song or dance or performance that ties them to their land. Both of these were entered as evidence on behalf of the appellants. The most significant evidence of spiritual connection between the Houses and their territory was a feast hall where the Gitksan and Wet’suwet’en people tell and retell their stories and identify their territories to remind themselves of the sacred connection that they have with their lands. The feast has a ceremonial purpose but is also used for making important decisions.

(Delgamuukw v. British Columbia [1997] 3 SCR 1010, 1997 SCC 23799)

Delgamuukw also established more guidelines to follow, post-Sparrow, when proving Aboriginal title. This included guidelines on the use of oral history as evidence. In paragraph 143 of Delgamuukw, the court stated that the following preconditions will be enough to demonstrate that the occupancy of the land is “sufficiently important to be of central significance to the culture of the claimants” (Delgamuukw v. British Columbia, para. 151):

- the land must have been occupied prior to sovereignty;

- if present occupation is relied on as proof of occupation pre-sovereignty, there must be a continuity between present and pre-sovereignty occupation; and

- at sovereignty, that occupation must have been exclusive. (para. 143)

However, in spite of the gains made in the Delgamuukw decision, the development of agriculture, forestry, mining, hydroelectric power, building infrastructure could ALL justify infringement of those rights, as per the Sparrow Test. Remember, the Sparrow Test laid out the criteria for justifying a breach of Aboriginal title. Delgamuukw did not overturn this test.

Tsilhqot’in Nation v. British Columbia [2014] 2 SCR 257

Following Delgamuukw, many other cases tested the decision and guidelines emerging from Delgamuukw. One of these is Tsilhqot’in Nation, which affirmed that Aboriginal title constitutes a beneficial interest in the land, the underlying control of which is retained by the Crown (Tsilhqot’in Nation v. British Columbia, para 70). The rights conferred by Aboriginal title include the right to decide how the land will be used; to enjoy, occupy, and possess the land; and to proactively use and manage the land, including its natural resources (para 73).

Moreover, clarifying Sparrow, the Crown can override Aboriginal title if

- the Crown carried out consultation and accommodation;

- the Crown’s actions are supported by “compelling and substantial objective”; and

- the Crown’s actions consistent with fiduciary obligation to Aboriginal body (para 77).

Sovereignty Versus Rule of Law

- Is settler-colonial Canadian law sovereign over everyone on the territory that is now known as Canada?

- Has the Crown exempted itself from the rule of law and exercised arbitrary, unbridled power over Indigenous people?

Responses to both these questions may be complicated in detail, but simple in fact:

- NO, settler-colonial Canadian law merely asserted itself as sovereign over all the territory that is Canada. Indigenous people call for a recognition of their sovereignty over their land, which is a sovereignty that predates British occupation, and was recognized in the Royal Proclamation, 1763.

- YES, the Crown has acted above the rule of law. The seizure of sovereignty and establishing the Indian Act as an arbitrator of legal status granted, or denied, to Indigenous people places the Crown (and the Canadian government) above the law.

Wet’suwet’en Nation and Coastal GarLink Pipeline

The Unistʼotʼen Clan has held a checkpoint on their land since 2010. This blockade has prevented pipeline construction crews from entering the area because the Office of Hereditary Chiefs of the Wet’suwet’en has not granted permission. While some Band Chiefs have approved of the pipeline, thereby satisfying the “duty to consult and accommodate” as per Tsilhqot’in Nation v. British Columbia, Hereditary Chiefs have not (para. 17). The validity of the Wet’suwet’en House and Clan system was verified in the Delgamuukw Supreme Court decision that upholds the authority of the hereditary system on Wet’suwet’en traditional territories. Nevertheless, in early 2020, the British Columbia Supreme Court injunction allowed access to the RCMP who violently arrested twenty-eight protestors. The British Columbian government, supported by the federal government, maintain that there is a “compelling and substantial objective,” including a clear economic justification, for the Coastal GasLink pipeline to be built (para. 77).

The Wet’suwet’en standoff — in Unist’ot’en and Gidimt’en — continued into 2022. These standoffs, and raids follow a long history of clashes between Indigenous people affirming their section 35 Aboriginal rights confronting economically justified, government-backed infrastructural development that is legally “allowed” to infringe on Aboriginal rights and treaty.

In February 2022, Gidimt’en land defenders made a submission to the United Nations Human Rights Council’s Expert Mechanism on the Rights of Indigenous People on the “Militarization of Wet’suwet’en Lands and Canada’s Ongoing Violations.” The submission was co-authored by leading legal, academic, and human rights experts in Canada and is supported by over two dozen organizations such as the Union of B.C. Indian Chiefs and Amnesty International Canada.

Please watch the video below and follow the links indicated under Further Reading to familiarise yourself with the struggle as articulated by Wet’suwet’en people in Unist’ot’en and Gidimt’en.

“The Wet’suwet’en people, under the governance of their Hereditary Chiefs, are standing in the way of the largest fracking project in Canadian history. Our medicines, our berries, our food, the animals, our water, our culture, our homes are all here since time immemorial. We will never abandon our children to live in a world with no clean water. We uphold our ancestral responsibilities. There will be no pipelines on Wet’suwet’en territory.” – Sleydo’ Molly Wickham