Feminist Legal Theory and Intersectionality

In Canada:

- Approximately every six days, a woman in Canada is killed by her intimate partner. Out of the eighty-three police-reported intimate partner homicides in 2014, sixty-seven of the victims—over 80 percent—were women. On any given night in Canada, 3,491 women and their 2,724 children sleep in shelters to escape abuse.

- On any given night in Canada, about three hundred women and children are turned away because shelters are already full.

- There were 1,181 cases of missing or murdered Aboriginal women in Canada between 1980 and 2012, according to the RCMP. However, according to grassroots organizations and the Minister of the Status of Women, the number is much higher, closer to four thousand.

- Aboriginal women are killed at six times the rate of non-Aboriginal women.

- Women are at greater risk of experiencing elder abuse from a family member, accounting for 60 percent of senior survivors of family violence. (Canadian Women’s Foundation 2021)

Remember last week’s content where we looked at how law is an ideology that reflects the power of the class that holds control of the modes of production? Keep that Marxist jurisprudential perspective in mind as we explore how Marxist jurisprudence intersects with feminist legal theory and critical race theory.

You are equal because you are male. You are male because you are equal... --- (MacKinnon 1983, 644, 658)

Feminist Critiques of Law

Before Suffrage: Rights of Women

In 1789, at the cusp of the French Revolution, the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen, (French: Declaration des Droits de l’Homme et du Citoyen) was written as one of the basic charters of human liberties. Inspired by Enlightenment thinkers such as Montesquieu, Rosseau, as well as by the events in Haiti that lead to the Haitian Revolution (see “Atlantic Freedoms” by Laurent Dubois for a full account), the rights of man are seen as the precursor to modern human rights.

The Rights of Man and of the Citizen affirmed that these rights were natural, inalienable, and sacred. All men were affirmed to be born free and equal, and political association (including national membership) was important for the purpose of maintaining these rights.

In response to the Rights of Man, Olympe de Gouges (1748–1793), a playwright, wrote a companion declaration: the Declaration of the Rights of Women and the Female Citizen (1791). De Gouges affirmed that the revolution will only take effect when all women become fully aware of their deplorable condition, and of the rights they have lost in society.

She famously stated that where “woman has the right to mount the scaffold; she must equally have the right to mount the rostrum,” (de Gouges 1791) meaning that if women are to be punished, executed by the law, then they must also have the right to influence this same law. She was also an advocate of equality in marriage. Tragically, as Olympe de Gouges’s writing became more politicized and outspoken, she was targeted by the Jacobins and executed in 1793. Many have interpreted her execution as an attempt to warn, and silence, other women who advocated for women’s rights (see Moussett 2007).

Around the same time, in 1792 England, Mary Wollstonecraft (1759–1797) published A Vindication of the Rights of Women: With Strictures on Political and Moral Subjects. This pamphlet argued that women, and their education, were essential to the nation: “To render women truly useful members of society, I argue that they should be led, by having their understandings cultivated on a large scale, to acquire a rational affection for their country, founded on knowledge, because it is obvious that we are little interested about what we do not understand …” (Wollstonecraft 1792).

Like her French counterpart, Wollstonecraft’s work received bitter criticism and her feminist principles were largely discredited. Wollstonecraft died after giving birth to her daughter, Mary Shelley, who went on to write the famous, and much referenced, Frankenstein (1818) (see Richardson 2014).

Suffrage Movements

Suffrage movements in the UK and throughout the Commonwealth fought to extend voting rights, suffrage, to women.

The 1881 Married Women’s Property Act in the UK allowed women to own property in their own name, but this was, by virtue of property ownership in the 19th century, a law that was significantly limited in that it only impacted a small proportion of wealthy women.

The Suffragists (National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies) were established in 1897. These were law-abiding women who relied on educational work, petitions, public meetings, and consistent lobbying of MPs to bring attention to women’s suffrage. The Suffragettes (Women’s Social and Political Union), established in 1903, were associated with a more militant approach. Suffragettes believed that peaceful methods had proved to be ineffective and thus their motto became Deeds Not Words. Suffragettes used tactics such as going on prison hunger strikes in protest of being treated as criminals. These women suffered force-feeding in their attempts to gain political-prisoner status.

Following the First World War, the Representation of the People Act of 1918 granted the vote to women over the age of thirty who met a property qualification — namely, they had to be registered property occupiers (or married to a registered property occupier). The same act gave the vote to all men over the age of twenty-one.

In 1928, the amendment to the Representation of the People Act granted women in the UK, and those under British legal jurisdiction, the vote, regardless of property ownership.

Liberal and Cultural Feminisms

There were many ways in which attention to women under the law shifted and changed throughout the 20th century, in particular following World War II. However, due to the constraints in our time and space here, let’s leap to the 1970s and 1980s, when women were increasingly present in the workplace and represented in global political bodies, such as the United Nations.

The United Nations Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW), passed in 1979 by the UN General Assembly, was a significant global recognition of the discrimination and violence faced by women around the world. Recognition by a governing body, such as the UN, was applauded by liberal feminist perspectives, who believe that equality in politics, law, economy, and society are key to ensuring that women will not be discriminated against. The struggle for women to gain equality with men contrast with a different feminist perspective in the 1980s and 1990s, cultural feminism, which drew attention to the qualities of womanhood. For some, this was essentialized as motherhood, and for others this was attention to how care responsibilities are socialized as “women’s work” (see MacKay 2019 in the next Further Reading box).

The liberal feminist approach sought equality based on the fact that women are disadvantaged throughout the world and disproportionately targeted by sexual violence (see World Health Organization 2021). For instance, female rape has been recognised as an exercise of oppression and domination in war, violent conflict, and intimate relationships. This does not deny the reality that all genders can be victims of serious sexual assault and rape. Nevertheless, liberal feminist perspectives tend(ed) to focus specifically on the effect of rape and sexual violence against women.

In Canada

Canada’s Criminal Code has no specific “rape” provision. Instead, it defines assault and provides for a specific punishment for “sexual assault”. In defining “assault”, the Code includes physical contact and threats. However, other jurisdictions such as the US and the UK define rape as ‘penal penetration of the anus or vagina’. The fact that penal penetration is specified in the definition of rape means that statistically it is much more common for rape to involve a male perpetrator and female victim. Notwithstanding, violent sexual assault and rape is a crime that can be, and deplorably is, committed onto all genders.

The cultural feminist approach sought an ethic of care, which highlighted that women’s political aims are also connected to their role as carers. Women’s role as carers is not necessarily natural, but it is socialized such that women disproportionately have care responsibilities in society more than men.

Feminist Approaches to Law

Since the early 2000s, many fields of law whether in legal practice, legal education, or legal scholarship have included attention to how women are disproportionately affected, often negatively, by law.

For instance:

- family law: family rights, child custody, reproduction rights, etc.

- criminal law: domestic violence, rape and sexual assault, harassment, revenge porn, etc.

- access to justice: race, class, education, patriarchal family structures where access to finances can be withheld from women, etc.

- labour law: discrimination in the workplace, harassment, care work, child care, social reproduction, sex work, etc.

Law as Gendered

In 1983, Catharine MacKinnon (b. 1946) published a monumental article articulating a feminist legal perspective that identified structural misogyny, along with sexualized racism and class inequalities. MacKinnon is famous for pioneering the legal claim for sexual harassment in the USA. And, in 2000 MacKinnon represented Bosnian women survivors of Serbian sexual atrocities at the ICC (Kadic v. Karadzic). This case was pivotal in establishing legal recognition of rape in genocide, in other words the use of rape in war as a war crime.

Catharine MacKinnon is a professor of law at the University of Michigan. She has been a visiting professor at Harvard Law School and was the Special Adviser to the International Criminal Court (ICC) from 2008–2012.

As a contribution to feminist legal theory, MacKinnon’s work highlights how sexual identity is constructed through a gender hierarchy where women are subordinated. Building from Marxist jurisprudence, MacKinnon compares a theory of the state (Marxist) with a theory of power (gendered): the liberal state legitimizes social order, promising that the state will provide. The Marxist approach legitimizes civil society, promising that the people will provide. Both, according to MacKinnon, hold no space for feminism. MacKinnon asserts that the law sees and treats women as the “male gaze” sees and treats women: as subordinate and less than.

As a beginning, I propose that the state is male in the feminist sense. The law sees and treats women the way men see and treat women. The liberal state coercively and authoritatively constitutes the social order in the interest of men as a gender, through its legitimizing norms, relation to society, and substantive policies. It achieves this through embodying and ensuring male control over women’s sexuality at every level, occasionally cushioning, qualifying, or de jure prohibiting its excesses when necessary to its normalization. Substantively, the way the male point of view frames an experience is the way it is framed by state policy --(MacKinnon 1983, 644)

Key Arguments from MacKinnon (1983):

- Objectivity, neutrality, and universality in law denies sex inequality that creates the dominant point of view/perspective/norm (636, 639, 655).

- Rape is a legally constructed example of the dominance of “male law” or patriarchal law. This dominance is identified as systemic and hegemonic (636).

- How is rape legally constructed? Under conditions of male dominance (647):

- spousal rape: was deemed legally impossible before the following case law:

- Canada’s 1983 Bill C-127

- the UK’s decision in the case R v. R (1991)

- not criminalized in fifty-two states until 2011

- intimate, personal, non-consensual rape is often considered as not really rape (648)

- non-consent demonstrates how men dominate, while women have to choose (652–5)

- consent given in private is assumed unless it is disproven. Meanwhile, the law does not question who constructed the “private” , and who has power over the “private” (656)

- spousal rape: was deemed legally impossible before the following case law:

- How is rape legally constructed? Under conditions of male dominance (647):

- The state, and its law, is male in the feminist sense (644–5).

- The goal of feminism and feminist legal work is to “uncover and claim as valid the experience of women, the major content of which is the devalidation of women’s experience” (638).

Catharine MacKinnon writing about

#MeTooin 2017: “As stunning as the revelations have been to those who failed to face the long-known real numbers, the structural and systemic underbelly of this dynamic has only begun to be revealed.” -- (MacKinnon 2017)

Critiques of MacKinnon’s Feminist Legal Theory

Feminist critical and legal theorist Drucilla Cornell published a critique of MacKinnon where she problematized MacKinnon’s focus on women as victims. Cornell argued that there was little space within MacKinnon’s theory for women to be active agents in and against the male law (see Cornell 1991).

Carole Vance and Janet Halley, although each feminist legal scholars writing on distinct themes, both agreed that MacKinnon’s choice “. . .to speak only of sexual violence and oppression ignores women’s experience of sexual agency and choice and unwittingly increases the sexual terror and despair in which women live” (Bazelon 2015).

But perhaps even more obvious are critiques of MacKinnon’s flawed construction of female sexuality, which essentializes gender and race at the expense of Queer identities and trans communities.

Angela Harris (b. 1961), a professor of law at University of California, Davis, addressed the essentialization of race in feminist legal theory, in particular Catharine MacKinnon’s work.

Harris highlights how feminist legal theory can continue epistemic violence when gender is essentialized in a way that silences some voices to privilege others. The voices that are silenced turn out to be the same voices silenced by the mainstream: racial minorities, persons with disabilities, and non-binary or trans persons. To be fully subversive, Harris argues that the methodology of feminist legal theory must challenge not only law’s content but its tendency to privilege the abstract and unitary voices.

This means that feminist legal theory must not be limited by “women for women.” It must counteract victim narratives. Feminist legal theory must deeply, fundamentally question power and empowerment and bring attention to interlocking systems of oppression and “intersectionality.”

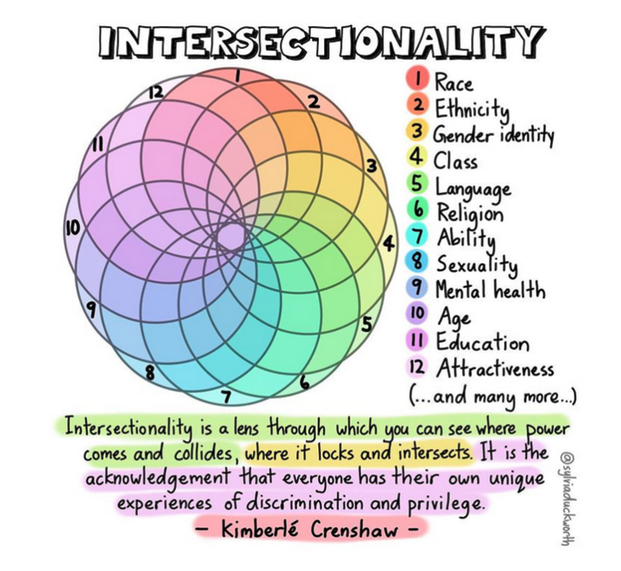

Intersectionality

Kimberlé Crenshaw coined the term “intersectionality” in her 1991 article “Mapping the Margins.” Since then, Crenshaw’s term has taken flight and is currently part of many discourses that bring attention to the ways our identities, histories, and contexts inform, cooperate, and exacerbate our experiences — often oppressive — with power, politics, violence, and law. It has been applied to law, health, politics, economics, finances, population demographics and housing, access to education, access to justice, and many other fields.

A law professor at Columbia, Crenshaw’s work on intersectionality was influential in the drafting of the equality clause in the South African Constitution. She has contributed to analyses of race and gender discrimination for the United Nations and coordinated NGO efforts to ensure the inclusion of gender in the World Conference Against Racism conference declaration.

Intersectionality adds to feminist legal theory by reminding legal critique of the multifaceted systems of oppression that modern law upholds. This includes the subjugation of feminist theory to the “male law” and discriminatory, oppressive, often violent experiences of women based on their gender. But also the interlocking systems of oppression that are exacerbated by factors of race, dis/ability, socio-economic status or class, education, ethnicity, and so on.

Audre Lorde (1934–1992), a prominent writer and poet, expressed her own experience of intersectionality:

As a Black lesbian feminist comfortable with the many different ingredients of my identity, and a woman committed to racial and sexual freedom from oppression, I find I am constantly being encouraged to pluck out some one aspect of myself and present this as the meaningful whole, eclipsing or denying the other parts of self. -- (Lorde 1984, 120)

Ultimately, feminist legal theory highlights the patriarchal, exclusive nature of modern law. Feminist legal theory’s emergence through history, including diverse voices that maintain the vital need for feminist theory to resist essentializing femininity at the expense of marginalizing voices of women of colour, women with disabilities, Indigenous women, trans women and many others continues. Feminist legal theory and intersectionality urge us to question who is the law for?

Women have traditionally been kept out of the public, political sphere, and this has meant that law, politics, economics, and culture have developed in ways that suppress and oppress women’s experiences and voices. Some feminist legal theory works toward inclusion and equality within the legal systems and structures of governance. Other feminist legal theory works toward a radical intersectional approach that challenges the very foundations of patriarchal, capitalist, colonial law. There is no right or wrong here. The theories and movements are about resisting an oppressive structure of law to make law and legal systems more inclusive and intersectional.

Remember our discussion of epistemic violence in Week 6, when we explored Kenrick McRae’s experience with the Montreal police? Epistemic violence is when one version, one narrative of knowledge is privileged above all other ways of knowing to the extent that other forms of knowledge are deemed illegitimate and erased. To be “free,” to have “rights,” to have the “law on your side,” one must subscribe to particular cultural, economic, and social norms. But, as we learned from Marxist jurisprudence, these norms are not universal but produced, performed, and historically specific.

In the words of Jacqueline Rose,

“Let feminism, then, be the place in our culture that asks everyone, women and men, to recognize the failure of the present dispensation … Where the most painful aspects of our inner world do not have to hide from the light … The feminism I am calling for would have the courage of its contradictions … Such a feminism would accept what it is to falter and suffer inwardly, while still laying out its charge sheet of injustice. This might just, I allow myself to think, be an immense relief for many of both sexes. It is, for me, what feminism uniquely has to bring to the increasingly dark times we live in” (Rose 2014).

Next week, we will dig deeper into epistemic violence as we explore Canadian law and Indigenous sovereignty in Canada.